1. American Bittern

The American bittern is a stocky brown heron with a black stripe on the whitish neck. The upperparts are streaky brown. In flight, the outer wing appears blackish. This secretive bird can be found, albeit infrequently, in Wisconsin’s marshes and along the edges of lakes and ponds. A master of disguise, the bittern freezes in an upright position when alarmed, helping it blend in with the cattails or other wetland plants. Unlike many members of the heron family, bitterns are loners.

The American bittern is the only member of the heron family more common in the northern half of the state, roughly north of a line from La Crosse to Sheboygan, than the south. They are common migrants, usually appearing around mid-April and leaving by early October. Many of these spring birds move on, while others stay, nesting primarily in the northern and central sections of the state.

In Wisconsin, bitterns have been found nesting among the cattails of the Trempealeau National Wildlife Refuge along the Mississippi River, in the Phantom flowage of Crex Meadows, in northwestern Wisconsin, and in the White River Wildlife Area in Green Lake County. The nest is a modest pile of dried reeds or similar plant material.

Bitterns feed primarily on crayfish and frogs, but also take occasional insects, fish, reptiles, and small mammals with their long and sturdy bills. They seldom sit in trees, preferring to stay hidden among the reeds.

The bittern’s unusual song has been likened to an old wooden water pump and has given rise to a number of interesting nicknames: thunderpumper, bog bull, stake-driver, and others.

2. American White Pelican

Massive birds with nine-foot wingspans, American white pelicans weigh in at about sixteen pounds. In flight, birds appear all white except for their black flight feathers. Unlike brown pelicans, which are well-adapted for diving for fish, American white pelicans catch fish while swimming in small groups, eating an average of three pounds of fish per day. The pouch of the large yellow-orange bill expands like a balloon when thrust into the water.

When thinking of Wisconsin birds, pelicans probably aren’t the first to come to mind. However, early records suggest that American white pelicans were common migrants along the Mississippi River in Wisconsin before 1850. According to Sam Robbins’ Wisconsin Birdlife, in the 1660s explorer Nicholas Perrot wrote, “Pelicans are very common, but they have an oily flavor…which is so disagreeable that it is impossible to eat them.”

The American white pelican was a rare migrant and summer visitor in Wisconsin through most of the twentieth century, but now nests in several locations throughout the state. In Brown County, pelicans nest on Cat Island, with large numbers often seen on a nearby sandbar. In Horicon Marsh, the birds nest on Cattail, Pelican, and Snag Islands. The nests are simple depressions on the ground lined with dried vegetation. Wisconsin’s pelicans leave the nesting grounds in September.

During migration, also look for American white pelicans in the Trempealeau National Wildlife Refuge along the Mississippi River, where they are often seen for several weeks in May. The birds can sometimes be seen circling high overhead, riding thermals.

3. Bobolink

The melodic bobolink is a medium-sized bird of open grassland, with a short tail and short conical bill. Male bobolinks are black in early summer, with a distinctive yellow nape, but molt to a buffy, streaked plumage in late summer. In his Field Guide to the Birds, Roger Tory Peterson likened the male’s breeding plumage to a “dress suit on backward.” Females and young are yellowish brown above, with paler underparts.

Members of the blackbird family, the bobolinks’ spring arrival in Wisconsin usually occurs in May, months later than red-winged blackbirds and others of this species. Male bobolinks reach their nesting grounds in the state before females, showing a distinct preference for wild rice, timothy hay, and other grass meadows.

The male’s exuberant courtship song is often described as “bubbly.” Sam Robbins wrote in Wisconsin Birdlife that the bobolink could “bring an entire meadow to life with its lilting, rollicking melody.”

Bobolinks are common migrants and summer residents throughout state, although less common in the far north. Their nests are built on the ground, concealed by tall grass. Wisconsin Breeding Bird Survey statistics indicate that nesting numbers have declined in the past three decades, probably a result of changed agricultural practices.

In Wisconsin, fall migration starts in late July, with bobolink flocks growing larger as summer wears on. These long-distance migrants winter in southern South America, making a round-trip of about 12,500 miles each year. The Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology estimates that a banded female known to be at least nine years old had traveled a distance equal to circumnavigating the globe four and one-half times.

4. Chestnut-sided Warbler

In breeding plumage, the male chestnut-sided warbler sports a greenish-yellow forehead, black mustache, and white underparts with chestnut streaks along the sides. The streaks and mustache are less prominent in females. Immature birds are yellow-green above and whitish below.

In early May, listen for this garrulous warbler’s distinctive courtship song, a series of notes accented at the end: pleased, pleased, pleased to MEETCHA. No johnny one-notes, chestnut-sided males use different songs for different purposes; a second song, usually performed at the edge of the warbler’s territory, is used to deter competing males.

In Birds of North America, Kenn Kaufman notes that this species is apparently more numerous today than in years past, perhaps because the clearing of forests created more of the brushy habitat the bird prefers. The chestnut-sided’s preference for low shrubbery and small trees makes them relatively easy to find as they hop about the understory, alleviating the springtime condition known by many as “warbler neck.”

Chestnut-sided warblers are common migrants throughout the state, usually arriving in southern Wisconsin during the first few days of May. They are common summer residents in the north, abounding in areas with cutover brush and understory. Breeding Bird Survey data from the northern third of the state indicates that this species is outnumbered among warblers only by the ovenbird and common yellowthroat.

In Wisconsin, fall migration occurs from mid-August through early October. Upon reaching their Central American wintering grounds, chestnut-sided warblers engage in mixed-flock foraging with resident antwrens and tropical warblers.

5. Northern Shoveler

During breeding season, roughly from December to May, the male northern shoveler has a dark green head, white breast, pale blue wing patches, and rusty sides. At a distance, the male resembles a mallard, but the large shovel-shaped bill makes this species recognizable in all plumages. Shovelers maintain a low profile, sitting lower than mallards and with bill pointed toward the water. Female shovelers have brownish mottled feathers and a blue wing patch.

You will often find this “spoonbill” in shallow water near the grassy edge of a pond or lake. These filter feeders lower their spatulate bills to take in water, then use the comb-like teeth on their bills to strain out plants and aquatic animals. Shallow ponds with muddy bottoms are the shoveler’s preferred habitat.

Although Wisconsin lies east of the shoveler’s main winter and summer range, many birds pass through the state during migration. The first birds usually arrive in southern Wisconsin by mid-March. Look for them in Horicon Marsh, which sometimes has more than one thousand spread out over its extensive wetlands. In spring, you can find shovelers throughout much of the state, including Little Lake Butte des Morts near Neenah/Menasha. Wintering birds have also been found on the open water of ponds and shallow lakes in Dane and Milwaukee Counties.

Wisconsin’s breeding population of shovelers is relatively small, with the largest number believed to be in Horicon Marsh. Shovelers have also nested in Rush Lake, located in Winnebago County, and in Dunn County in northwestern Wisconsin.

6. Northern Shrike

The northern shrike is a robin-sized bird with a distinctive black mask that ends at the bill. The wings are black with white patches, which are most visible in flight. The black tail has white outer feathers. Northern shrikes have bicolored bills, while the loggerhead shrike, very similar in appearance and more common to the south, has an all-black bill.

If you see a lone robin-sized bird perched atop a tree in the middle of winter, there’s a good chance it’s a northern shrike. Solitary hunters, shrikes sometimes resemble treetop ornaments as they scope out possibilities for the next meal. The northern shrike’s species name excubitor means “sentinel.”

Shrikes are the only songbirds that routinely prey on other vertebrates, which are killed by a blow from the hook-tipped bill, usually on the back of the head. Birds as large as blue jays are taken, as well as smaller “portions” such as black-capped chickadees and sparrows. The shrike’s diet also includes small mammals and insects. Because shrikes sometime store uneaten prey by impaling it on thorns or barbed wire, they have been dubbed “butcherbirds.”

Although the number of northern shrikes tallied during the state’s annual Christmas Bird Count has risen steadily since 1965, they are still uncommon winter residents and migrants. Shrikes sometimes show up as uninvited guests at Wisconsin bird feeders in January and February. Most wintering birds leave the state in March, heading northward to spruce stands and alder thickets at the edge of the tundra.

7. Pileated Woodpecker

In North America, this crow-sized woodpecker is second in size only to the ivory-billed woodpecker. Both male and female are primarily black, with a prominent red crest. Adult males have a red forehead and mustache, which are black on females. In flight, the pileated’s large white wing patches are visible. The genus name is derived from the Greek words drys, meaning “tree,” and kopis, meaning “cleaver or dagger.” The word pileatus means “crested.”

If you’re walking along the river bottom in Wyalusing State Park, you may hear loud drumming in the area or notice large rectangular holes in many of the trees. These distinctive excavations, made by hungry pileated woodpeckers, may be several inches wide and up to a foot long. The nearby water and damp environment promote wood rot, which in turn invites carpenter ants —the pileated’s favored bill of fare. The woodpecker uses its long, brushy tongue to extract ants from the cavity.

In the mid-1800s, pileated woodpeckers could be found anywhere in the state where there were mature trees, but mass felling of forests in the latter part of the century resulted in the species decline here and throughout North America. Some biologists believe the spread of Dutch elm disease in the mid-twentieth century helped increase pileated populations by providing more numerous nesting sites. The species’ numbers have been steadily increasing on Wisconsin’s Christmas Bird Count over the past thirty years, with pileateds even showing up at bird feeders to dine on suet.

8. Sandhill Crane

Photo by John J. Mosesso via Wiki Commons

Adult sandhill cranes are all gray, with yellow eyes, a red patch on the crest of the head, and black bills, legs, and feet. Immature birds are primarily brown. A bushy tuft of feathers, sometimes called a bustle, covers the sandhill’s rump. In spring, some birds sport brown “makeup,” mud the birds have applied to their feathers to better camouflage themselves in the dried vegetation.

Unlike herons, which fly with necks folded, cranes fly with their necks fully extended, often announcing themselves with a guttural, crowing rattle. In flight, the sandhill’s wings have an upstroke that also helps distinguish it from great blue herons.

The sandhill is one of two crane species found in North America. The other, the magnificent whooping crane, is benefiting from a reintroduction program centered in Wisconsin.

A 1936 estimate put the number of breeding pairs of sandhills in Wisconsin at twenty-five. Seventy years later, sandhills are common summer residents throughout the state. The sandhill nest, which may float while anchored to standing plants, is located among marsh vegetation. In fall, sandhills congregate by the thousands in large wetland areas such as central Wisconsin’s Sandhill State Wildlife Area and Necedah National Wildlife Refuge and in Crex Meadows in the northwestern part of the state.

Sandhills winter in Florida, then return to Wisconsin’s marshes in March. Look for them in open fields, where they feed on waste grain during migration. Omnivores, sandhills peck at the ground or probe the mud while walking slowly through fields or marshes. They often feed on waste seed in agricultural fields, but will also eat tubers, invertebrates, and even small vertebrate animals.

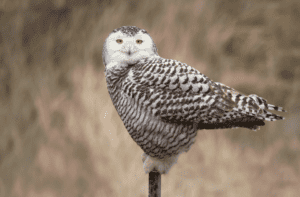

9. Snowy Owl

The snowy is a large white owl with a rounded head and yellow eyes. The amount of dark barring or flecking is variable; older males are almost pure white, while younger females are heavily marked. Snowies appear more agile in flight than other owls. Snowy owls summer on the northern tundra, where they hunt lemmings and other rodents by day. Males woo potential mates by “dancing” stiffly with wings outstretched, sometimes offering a dead lemming as a gift.

In years when low lemming populations send these powerful predators south, snowy owls can be found throughout Wisconsin (there are records for all but four counties). During these “flight years,” the impressive birds are often seen sitting on fence posts near open fields, around airports, or atop buildings in urban areas.

In Wisconsin, snowies usually arrive in mid- to late November, with most moving northward again in March. The birds are found most often in cities or near large areas of ice or water. Snowies are regularly seen in the industrial areas of Superior, frequently sitting on buildings and fences near the city’s high school. They often range south from the Fox River Valley to Dane and Milwaukee Counties in southern Wisconsin. In Green Bay, look for snowies along the bay shore and Fox River marshes. Across the state in La Crosse, the birds are often seen at the Municipal Airport. Sightings of banded snowy owls indicate that birds often return to the same wintering locations year after year.

Analysis of snowy owl pellets show that meadow voles are the rodents du jour during the birds’ stay in the state. Snowies are diurnal owls, hunting by day.

10. Tundra Swan

Although it has a wingspan of about seven feet, the tundra swan is the smallest North American swan. Adults are all white with black bills, often with a small yellow dot at the base. Young birds are dingy gray or brownish-white with a dark head and pinkish bill. The tundra swan’s bill is slightly dish-shaped or concave and smaller in proportion to its rounded head.

The bill of the trumpeter swan, in contrast, appears heavy and somewhat wedge-shaped in proportion to its large angular head. The best way to distinguish the two species is by their calls; tundra swans utter a nasal honking while flying in ribbon-like flocks, higher pitched than the bugling call of the trumpeter.

It might be said that tundra swans go against the flow: unlike many migrants, which travel in a north-south orientation, these swans take more of an east-west route as they travel from wintering grounds along the Atlantic coast to their breeding grounds in Alaska and Canada. In fall, large numbers of tundra swans pass through the Mississippi River valley corridor, usually arriving in mid- to late October and then leaving for their wintering grounds in November.

In fall, look for large numbers of swans at Rieck’s Lake Park in Alma, along the Mississippi River. They feed on tubers and weeds in the shallow water and fly up to fifteen miles inland to forage on waste grain or potatoes. When feeding in water, they can reach food three feet below the surface by upending themselves, with head straight down and tail up.