THUNK! It happens every day, sometimes three or four times a day during fall migration. I freeze, sifting the information coming into my ears and brain. Which window was it? How big a bird was it? How hard did it hit? Will it die?

Depending on the quality of the sound, I can decipher all these bits of information; I can pretty well tell whether it was a cardinal or a mourning dove, a goldfinch or a hummingbird. I can tell, based on the volume and tonal quality of the thunk, whether I will find a few floating feathers, a dazed bird, or a carcass in the shrubbery beneath the window. I don’t want to know these things, but I do. Our house, as much as we love it, is lethal to birds, and I have had entirely too much practice at this.

Atop our house, we’ve built a tower that stands 42 feet tall, expressly for watching birds. It’s got four huge plate-glass windows, one to a side; it’s practically all glass. Despite what you’d expect, birds almost never hit those windows. Because the tower room is so well lit, the windows don’t reflect the sky; they appear perfectly clear. So a bird flying toward the tower windows, hoping to pass through them, quickly perceives that it is about to fly into an enclosed space, and birds don’t like to do that.

My studio sits two floors directly below the tower. The lethal windows are the four along the north side of the house on the studio level below the tower. There’s a fifth deadly window looking out of our foyer.

Because I work in natural light, and rarely turn on the overhead tract lighting, the cavernous studio interior is much darker than the outside world. The windows’ north-facing orientation lends the studio a constant light that’s wonderful to work by, but it also ensures that they reflect the sky from dawn to dusk.

I’ve noticed that window strikes peak on overcast winter days, which is practically the only kind of winter day we have in the Mid-Ohio Valley.

When I go outside to assess the victim, I make a point of glancing at the window it hit, and it’s usually reflecting a perfect image of the sky and trees in our yard. No wonder the birds hit the glass; they think it’s sky.

When we planned the tower and studio construction, we anticipated window strikes, and learned upon researching the problem that windows set at an angle so that they reflect the ground instead of the sky have greatly reduced strikes.

Our contractor was willing to give it a try, but the manufacturer informed him that, although we were free to try it, doing so would void the warranty for the windows. Three had already proved defective and had to be replaced; trying anything fancy with their orientation would have meant we’d have to replace them out of pocket.

So we moved to Plan B, which was to affix preventative devices to the outside of the windows, hoping to warn the birds of their presence. Silhouettes stuck to the windows to break up the reflection of apparent sky had little effect on strikes. I put one up recently that came free in the mail as a bonus gift, touted as the solution to window strikes because it incorporates ultraviolet-activated designs that birds could perceive. That same afternoon, a rosette of mourning dove breast feathers appeared two inches to the right of the new decal.

For three winters, we used FeatherGuards, an ingenious product invented by BWD subscriber Stiles Thomas. FeatherGuards are simple but effective—a strand of monofilament strung with colored poultry feathers, with a suction cup on either end.We were gratified to find window strikes slowing to almost nothing soon after installing the guards, which we placed at one-foot intervals along the bank of windows.

On smaller windows in fairly sheltered locations, FeatherGuards may well be the most effective solution. We live on one of the highest ridgetops in Washington County, however. Days without wind are almost unheard of, and gusts of 40 to 50 mph are commonplace.

It wasn’t long before the ferocious winter winds ripped the guards from our windows, tangling them together in a hopeless knot. We eventually tired of hauling out the ladder and reapplying new FeatherGuards after each wind event. The winds on our ridgetop were just too much for them.

A manufacturer sent us a protective screen to try, claiming that it was the only real solution to window strikes. I had to concede that a nylon screen barrier over the window would work to stop window strikes cold.

But when we hung it in front of the studio window, the fine black window screening—the same kind used to stop insects—dimmed the clean north light I need for my work, stopped my photography, and made observation more difficult. We had to find a solution we could live with.

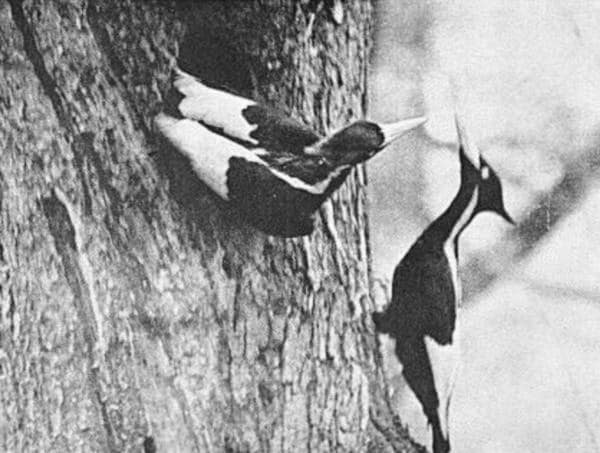

On a fall day when migration was at its peak, I had picked up a dead ovenbird and a young yellow-bellied sapsucker in rapid succession. I hadn’t gotten to know the ovenbird, but I had treasured that sapsucker, watching him slowly destroying the gray birches just outside the studio window.

I came inside, distraught, and decided to try hanging Mylar windsocks over the windows. I searched online and ordered the biggest, most ostentatious windsocks I could find. Two days, a 12-foot ladder, lots of scary teetering, and $70 later, a rainbow-colored assortment of windsocks, trailing three feet of finely cut Mylar fringe, fluttered and swung against the windows.

They were pretty tacky, but I was past caring about that, and had high hopes that they’d work. And then out of the stormy skies came Windy, leaning down to capture a moment and wad up and destroy $70 worth of windsocks while she was at it.

With great interest, I read ornithologist David Sibley’s blog, detailing his experiments with fluorescent highlighter pens. He drew patterns on the inside of his studio windows that would presumably be visible to birds, which are known to be sensitive to ultraviolet light—Thunk!

As I write, a male scarlet tanager in fall plumage hits the studio window. The tanager flies to a nearby birch, his bill agape, eyes open and bright, and sits as if wondering about the suddenly solid sky for about 40 seconds before flying off. He’ll probably make it. Where was I?

Oh, yes—fluorescent highlighters. Although he had high hopes, the results of Sibley’s experiments were equivocal. Of course, I scrounged yellow and orange highlighters and scribbled all over the inside of one of my windows, but I didn’t notice a big difference in the collisions relative to the other two. More data are needed. And more birds die in the meantime.

By the spring of 2008, I was heartily weary of hearing thunks. When my beloved red-bellied woodpecker friend Ruby killed herself against the window on May 23, I gritted my teeth and decided to end the killing once and for all.

Nice idea. I have too many big windows to do this. Currently using bird clings from Audubon which do help some. Could use more of them though. These clings are of several bird species. One day the hummingbird cling was being stared at by a real hummer, hovering about a foot away. Bet it wondered who that outsize hummer was (the cling not being life size).