A team of ornithologists organized by Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology has rediscovered at least one male ivory-billed woodpecker, alive and well and living in Arkansas. The news, which broke April 28, 2005, has turned the birding world upside down, and my heart inside out. I have been enchanted by ivory-billed woodpeckers since I was very young, and have written about them, painted them, and talked about them with some of the last living people to have seen them. My article, “Ivory-billed Woodpeckers,” which appeared in BWD’s May/June 1999 issue, elicited an unprecedented response from our readers, and remains a watershed piece for me.I lie awake at night, thinking about the implications of this ornithological bombshell. There is so much to think about. The first time we had a chance to save the ivory-billed woodpecker, we allowed it to slip away. Could we pull it back from the brink this time? — Julie Zickefoose.

Below is the text of a commentary, “The Ivory-bill, Found,” which Julie Zickefoose recorded for NPR’s All Things Considered on April 28, 2005.

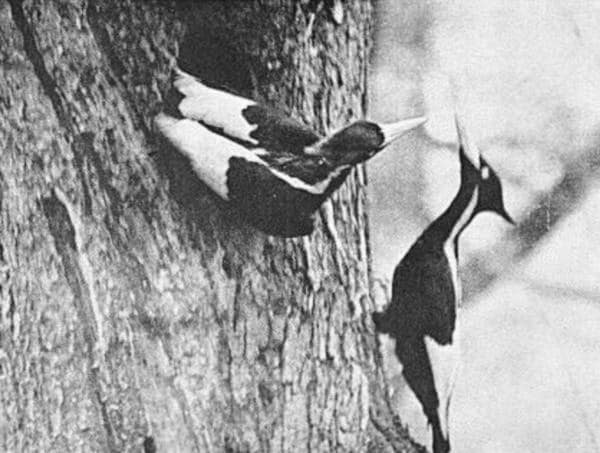

When I start thinking about ivory-billed woodpeckers, I find it hard to stop. They hitch and flap and peck around in my head; they have since I was eight years old. Ivory-bills make me think about large issues, like extinction, and small things, like the look in their eyes, the gloss of their jet-black feathers.

In the winter of 1998, I decided to interview the last living people to have seen the ivory-bill. I wanted to hear their voices, write down their words. The great bird artist, Don Eckelberry, brought the bird back for me. “She came trumpeting in to the roost, her big wings cleaving the air in strong, direct flight, and she alighted with one magnificent upward swoop.

Looking about wildly with her hysterical pale eyes, tossing her head from side to side — she hitched up the tree at a gallop, trumpeting all the way. I was tremendously impressed by the majestic and wild personality of this bird, its vigor, its almost frantic aliveness.” It was 1944, and Don was watching the last known living ivorybill in the (Tinsaw) River Bottom of Louisiana. Don Eckelberry is gone now, but the species, it seems, lives on.

After the first flood of cautious exultation on hearing the news, worry set in. Once the world knows about this-something that will take only hours in the Information Age– how will we handle the crowds of birders from Taiwan to Wales, Denmark to Buenos Aires that will converge on the Arkansas bottomlands? Even now, they’re booking flights, descending like grackles on a field of corn.

And I thought of California condors. When it became clear that the birds would vanish without extreme intervention, biologists set cannon nets over bait and captured them all, and the skies were emptied of this prehistoric relic. They were caged, their eggs taken from them, their young raised with lifelike puppets. And against all odds, it actually worked. There are condors circling southwestern skies again; condors laying their chalky eggs in natural cliff nests.

If there is one ivory-bill still alive, there have to be more. A reproducing population, making more ivorybills, generations enough to span sixty years. Must we trap them in their roost holes, and bundle them into cages, these mythic beings with their wild eyes and fiery crests? Given a choice between such intervention and certain extinction, and the intellect to consider it, what would an ivory-bill choose? I imagine it flying away, in a long, straight line, putting miles of swamp between it and the further workings of humanity.

In the bottomlands of Arkansas, at least one ivory-bill still hitches and raps and tosses his fluffy topknot, pounding his great white bill into bark. He’s defied us all. We’ve sent him countless messages with our saws and bulldozers. Leave or die out. Find somewhere else to live. This land is our land, now. And the bird didn’t hear us, he went on about his business; not dead, just missing in action; alive, defiantly, joyously alive. For those of us who have never been able to let the ivory-bill go, the vindication is bittersweet. They’ve found the ivorybill! Eureka!! Now what?