An Intriguing Trip

“Did you see what I just saw?” my wife demanded.

“Yep. There was definitely contact,” I replied as we sat in our pickup, parked on Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park in early June.

In the dim break of day, a female blue grouse scurried up a slope to the left of us and disappeared 40 feet away. A male blue grouse—who had just spent 10 minutes displaying for the apparently oblivious female and then marched up and struck her with his head—retreated to the other side of the road, not 20 feet from us. The male fanned his tail again, raised the yellow-orange comb over his eye, and revealed his red neck sac, but his display seemed lackluster now. Or were we just slipping into a soap-opera mindset?

What an intriguing trip this was turning out to be!

It all started on a January night at our kitchen table back in Great Falls, Montana. Sure we’d enjoyed seeing birds in places like Arizona and Texas, but what would make a satisfying bird trip to our own area?

We started mapping out sites. A chestnut-collared longspur leaping skyward here, a mountain bluebird on the barbed wire there. Add a flock of pygmy nuthatches bopping around comically in the ponderosas, a wailing common loon on a lake, a smattering of western tanagers for color, and a chance at a ptarmigan. When we were finished, we had planned a 417-mile loop that climbed up and over the Continental Divide, circling some of the nation’s finest wilderness. Together with jaunts off the circle, the route included prairie marshes and grasslands, varied forests, and alpine slopes, even Glacier National Park.

It was a trip for the mildly adventurous, being in grizzly bear country and involving many departures from the pavement, but there was nothing a passenger car couldn’t negotiate. Camping would be a convenient option because many of the sites were in campgrounds anyway, but lodging would never be impossibly far.

(Tip: Spend $55 [or less] on a can of bear spray and a holster to keep it at-the-ready. Avoid hiking alone and hiking at dawn, dusk, or night. Keep kids near.)

It was only when we read the paper later that we realized what a beauty we had—our route overlapped heavily with the newly created Northern Continental Divide Scenic Loop, laid out to showcase the Rockies.

But best of all was a weeklong testing of our route in the wet but birdy month of June.

Great Falls

Ulm Pishkun State Park is all about a cliff beside a prairie, where prehistoric Native Americans stampeded bison over the precipice. Stand at the top of the buffalo jump when the upper park opens at 7 a.m. and you’ll see sunlight raking across a sweeping view of buttes and, beyond them, mountains. A symphony of song floats upward, dominated by rock wrens on the cliff and lusty western meadowlarks on the prairie. No matter how we may have rushed pell-mell to get here, suddenly the desire to hurry tumbles out of us as we pause to savor this moment. Is there a better way to start the day?

Follow the path down the cliff to view the rock wrens, but save the prairie songsters for 8 a.m., when you can drive down to the visitor center and search out the grasshopper sparrows and Say’s phoebes, among others.

In the meantime, at the prairie dog town above the cliff, enjoy long-billed curlews as they work their way along. They’re a snap to pick out of a crowd of prairie dogs, but you’ll have to scope carefully for a burrowing owl. We don’t always find an owl, but we’ve already seen one on a fencepost as we approach the park. We’ve spotted a short-eared owl flying mothlike over the grasslands, too.

Benton Lake National Wildlife Refuge, to the north of Great Falls, has a different cast of prairie birds and a marsh crammed with waterfowl. As you turn onto the gravel road to headquarters, start looking at once for chestnut-collared longspurs, black-bellied birds perching on the grass. Down the way, marbled godwits wing across the prairie, and perhaps a sharp-tailed grouse peeks out below. A loggerhead shrike stands sentry above a shelterbelt, clay-colored sparrows fly near the edges, and a covey of gray partridge scurries below.

At last, the auto-tour route reaches the teeming marsh. Duck soup is the thought that comes to mind when we look across the water. Breeding ducks such as cinnamon teal abound, punctuated by eared grebes and surrounded by Wilson’s phalaropes spinning in the shallows. A colony of Franklin’s gulls makes considerable din, while raucous yellow-headed blackbirds k-k-kronk from the cattails. As if the place wasn’t noisy enough, willets and American avocets make loud protests from the shore and marsh wrens buzz among the cattails. The descending call of a sora adds a pleasant element to the cacophony, and the skies hold hovering common terns, Forster’s terns, and a flapping white-faced ibis. A prairie marsh in June is a busy place! As the road leaves the crowded waters, the meadowlark chorus is quiet by comparison.

Next the birding loop launches out across the prairie toward Augusta. This isn’t the time for a nap, though. A good number of species are likely to be found. You will find ferruginous hawk, bald and golden eagle, prairie falcon, and Swainson’s hawk, if not in the sky or on a post, sitting at the nest. There just aren’t many trees for prairie raptors to choose, so nest spotting is easy. Swainson’s hawk, a great horned owl, or a long-eared owl may be the prize. Fencelines may host Say’s phoebe, mountain bluebird, or upland sandpiper, meadows may boast sandhill cranes, and farther along the route, lakes may hold Barrow’s or common goldeneyes or even a trumpeter swan. Pronghorn are sure to show up, too.

Blackfoot/Seeley

The scenery changes quickly as Highway 200 heads up into the Rockies, reaching the Continental Divide just 13 miles from the plains. This brings a climate that is wetter, cloudier, and calmer, and trees that stand taller and closer.

The country drained by the Blackfoot and Clearwater rivers is dotted with many lakes. Swing into Brown’s Lake and pause to enjoy the beautiful red-necked grebes that sit on nests in a shallow arm of the lake. Such a contrast with the sagebrush on the other side of the road that hosts Brewer’s sparrow! Black terns cruise by and, when you get to the lake’s fishing access site, western tanagers will greet you. They are common birds on this side of the state, but they are so crayon-bright colorful in their red, yellow, and black plumage that we never tire of them.

Continue on to enter loon country, where you will usually find pairs on Upsata, Salmon, Placid, Inez, Alva, and Seeley lakes. Perhaps a loon will have a chick riding piggyback. Better yet, and more likely, you will thrill to the sounds of the loons as they wail, yodel, laugh, or hoot. This is a place to linger, but carefully. Loons are sensitive birds.

Around the loon lakes you’ll find new bird possibilities in the forest, such as gray jay, varied thrush, pileated woodpecker, red crossbills, and more. The Seeley Lake Ranger Station deserves intensive effort. A trail through old-growth forest serves as a return route for paddlers on the Clearwater Canoe Trail and includes a wildlife viewing blind on the way. The more open area around the ranger station attracts species like rufous hummingbird.

Follow Highway 83 back to Highway 20 and look sharp for western bluebirds in the last couple miles approaching the junction.

Missoula

Greenough Park, just north of I-90, is a city park with a birding trail (labeled as such!) along a babbling creek. Pygmy nuthatches party above you, American redstarts flick in the shrubs, and Bullock’s orioles fly high in the cottonwoods. Our personal favorite is the American dipper. Whirring along just a foot above the creek or perched on a streamside rock doing kneebends, the gray bird just can’t sit still. Here’s a songbird that thinks it can dive to its dinner…and does!

Blue Mountain, on the southwest side of town, was a bird-watching bonanza after a fire several years back charred many acres. Walking uphill from the nature trail the year after the burn, we heard an olive-sided flycatcher almost at once. Later it was the quiet, repeated sound of a bird flaking off bits of bark that alerted us to black-backed and three-toed woodpeckers, specialists in burned habitat. The open canopy made finding birds such as mountain bluebirds, Cooper’s hawk, and a Townsend’s solitaire easy.

(Tip: Avoid burn areas on windy days when snags may be falling.)

Driving farther up Blue Mountain and then walking along the road, we found MacGillivray’s warbler, Calliope hummingbird, ruffed grouse, and pileated woodpecker for our efforts. At the foot of Blue Mountain, MacClay Flats offers a second spot to find western bluebird and pygmy nuthatch along its walking trails to the Clark Fork.

National Bison Range

We think there’s a gravitational anomaly near the National Bison Range, because every time we get within an hour’s drive of it, we just seem to get pulled in. Red Sleep Mountain Drive (not for trailers) is the top draw here, and it will take a few hours to cover the 19-mile route because of all the stops you’ll want to make. Except for two hiking trails, visitors must stay at their cars due to the bison. Speaking of mammals, glass any pronghorns you see because they may have kids. Bison will have both calves and brown-headed cowbirds, once known as buffalo birds, tagging along. And check for bighorn sheep around the summit.

The headliner for us is the lazuli bunting, which looks vaguely patriotic in its plumage of rufous, white, and blue. Handsome! Along Headquarters Ridge you may see the buntings early on, along with the spotted towhee. If not, then perhaps along Pauline Creek, with its flycatchers, orioles, warblers, and occasional yellow-breasted chat. Or surely you’ll find buntings as you climb the switchbacks beyond. At the summit, Townsend’s solitaire and blue grouse often hang out near the road.

Flathead Lake

Kerr Dam’s overlook, southwest of Polson, strikes our fancy for a short stop. Climbing down the many steps, the entire stairway vibrates because of the cataract below, but not in an alarming way. Lazuli bunting, rock wren, violet-green swallow, and white-throated swift are the payoff for this detour.

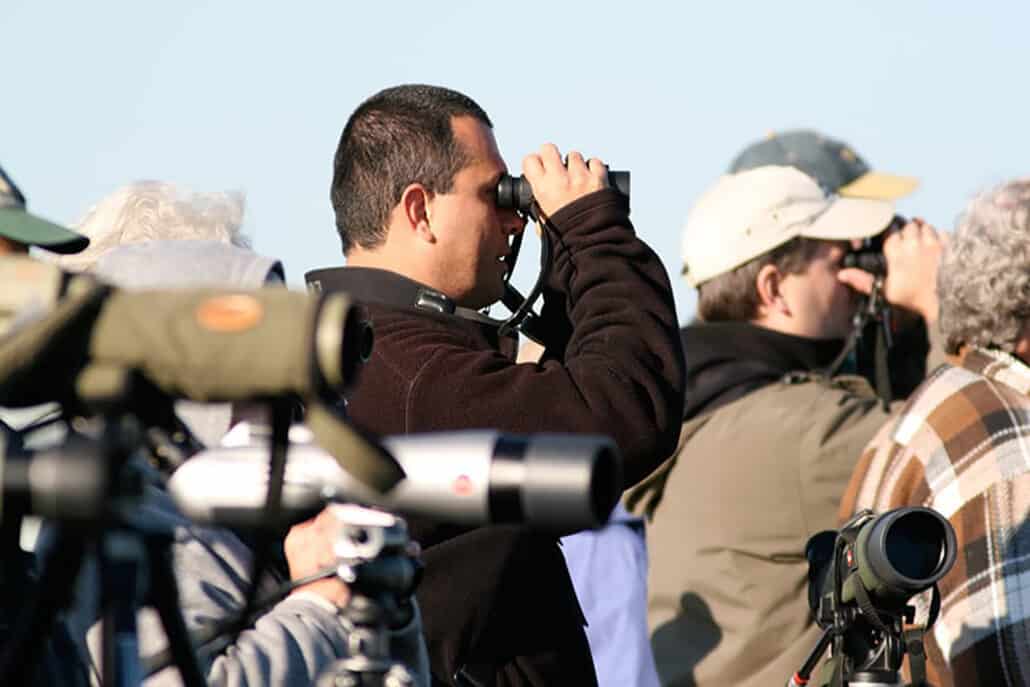

Next the loop moves up the east side of Flathead Lake, the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi, to Bigfork. This brings up a worthwhile option, the Bigfork Bird Festival in early June. Field trips range from the Bison Range to Glacier, supplying knowledgeable guides and a group to traipse with in grizzly country. The chance to network at evening events is a plus, too. You can probably count on one hand (or less) the other birders you’ve seen up until now.

South down the Swan River Valley, Swan Lake makes a worthwhile stop at the campground and day use area. MacGillivray’s warbler, Vaux’s swift, red-naped sapsucker, Townsend’s warbler, and Cassin’s finch are some of the plums here.

We have no explanation for Swan River National Wildlife Refuge. Maybe there’s something in the water that makes the birds there act out of character. Actually, only two species behave oddly. Wilson’s snipe have become social and absolutely litter the place, seeming to take turns so that at least one of them is winnowing at all times. Plus it’s a place where the reclusive American bittern often shows itself. Approach quietly, look with care, and by all means watch a good-sized bird that lands in the grasses. It may well be a bittern.

Glacier National Park

Going-to-the-Sun Road, a narrow, winding road not for trailers, runs through the heart of Glacier National Park.

Places to stop here include Trail of the Cedars, a mossy rainforest walk. Step over to the amphitheater, lie down on a wooden bench, and watch the sky for Vaux’s and black swifts, especially at dusk. The haunting, drawn-out notes of the varied thrush that will have visitors seeking out anyone with binoculars to find out what bird is making that sound. The thrush will almost invariably be singing from the top of the tall trees around you.

MacDonald Creek from the inlet to the lake up to the Sacred Dancing Cascades is another area of special interest. Harlequin ducks and dippers live along these turbulent waters.

Logan Pass on the Continental Divide is everybody’s favorite stop. People pitch slushy snowballs, ski a little, or look for mountain goats and bighorn sheep. For birders, the flower-filled meadows and stunted willows that emerge from the receding snows are a scene best completed by the sighting of a white-tailed ptarmigan. This is no guarantee, but the spectacular trail through the meadows to Hidden Lake Overlook is consolation in itself. Across the road, the Highline Trail is another good bet for gray-crowned rosy-finches.

For Lewis’s woodpecker, make the trip to the park’s Polebridge entrance, and continue a mile beyond, where white barkless snags rise from stands of young evergreens.

For chestnut-backed chickadees, Steller’s jays, and harlequin ducks try the Fish Creek picnic area and campground.

The Two Medicine corner of Glacier is another wildly scenic treat with a complement of birds such as Steller’s jay, pine grosbeak, and olive-sided flycatcher. Concentrate on the far end of the campground and the trail around the lake.

Glacier is an immense park with 700 miles of trails. Radd Icenoggle’s book, Birds in Place, identifies the forest types that match the species you have missed so far. Tailor a plan with help from the Hiker’s Guide to Glacier National Park or a visitor center.

Rocky Mountain Front

The Rocky Mountain Front, which stretches from Highway 2 to Highway 200, is where the Great Plains abruptly smack into the Rocky Mountains. No foothills here.

Drive down toward Choteau and take the road to Teton Pass (6,300 feet elevation) and the campground that lies at the end. At the campground sniff the evergreen-scented air and watch the mountain chickadees and mountain bluebirds flitting about. Working your way back down the road, you may find everything from Townsend’s solitaire, gray jay, and Cassin’s vireo to black-headed grosbeak, Wilson’s warbler, saw-whet owl, and veery. At times we’ve found bighorn sheep on the road and northern goshawk in the skies. As you exit the canyon, look for prairie falcon. Turn south on the Bellview Cutacross, and watch for Sprague’s pipit. As you reach Pine Butte Swamp, seek out alder flycatcher, sandhill crane, and, in the limber pines, Clark’s nutcracker. Try not to feel too bad about those car keys you misplace as you ponder a bird that buries 33,000 pine nuts annually, then has to find them to eat. (Miss the nutcracker? Try Gibson Reservoir on the Sun River.) Turning east onto Bellview Road, you’ll find bobolinks in wet meadows, long-billed curlews on the prairie, and thick-billed longspurs by the road as you head to Choteau.

Freezeout Lake Wildlife Management Area wraps up the trip. Similar to Benton Lake, it’s a prairie marsh that packs ’em in. Fill your eyes and ears with birds galore, and look especially for black-necked stilt, western and Clark’s grebes, and groups of white pelicans demonstrating teamwork in fishing. At the headquarters kiosk, pick up the leaflet “Birding Freezeout Lake” for expert guidance.

In the week the loop will take you, you are sure to see plenty of striking scenery, even in rainy June, and many feathered species. We’re willing to bet you see some striking bird behavior, too.

(Tip: Go early in the month for male harlequin ducks, the Bigfork Birding Festival, and peak birdsong and loon calls in the lower elevations. Go late in the month or even a week into July for best alpine access. Logan Pass typically opens during the first two weeks in June.)