“If you seek a beautiful peninsula, look about you.” is Michigan’s motto. Consisting of two peninsulas surrounded by the largest freshwater system in the world, the Great Lakes, there is indeed much beauty here. Michigan offers much of beauty and interest to the bird watcher and nature enthusiast. Michigan boasts 3,000 miles of shoreline, 11,000 interior lakes, 36,000 miles of rivers and streams, and the largest state forest system in the nation. With these diverse habitats, Michigan is particularly rich in bird species, with 421 species on the official state list as of July 31, 2003.

Although somewhat removed from the middle of the continent, Michigan’s birdlife provides a taste of north, south, east, and west. The majority of birds occurring here are decidedly eastern in flavor, but a more western influence is evidenced by the state’s small breeding populations of clay-colored sparrow, western meadowlark, and yellow-headed blackbird, and by the annual migrations, in small numbers, of more westerly species such as Franklin’s gull and Harris’s sparrow. Without doubt, Michigan is a northern state, and breeding warblers are well represented, in addition to breeding white-throated, Lincoln’s, and Le Conte’s sparrows, and hermit and Swainson’s thrushes.

There is also a far north component to Michigan’s birdlife in the presence of boreal breeding species, mainly in the Upper Peninsula, represented by breeding spruce grouse, black-backed woodpecker, gray jay, boreal chickadee, Connecticut warbler, and white-winged and red crossbills. In winter species from even farther north, including common redpolls, pine grosbeaks, white-winged and red crossbills, great gray, snowy, boreal, and northern hawk owls, move into Michigan on three- to five-year cycles, or irruptions. In the southernmost portions of Michigan several species occur, some near the northernmost limits of their distributions. These include red-bellied woodpecker, Acadian flycatcher, white-eyed vireo, Carolina wren, cerulean warbler, Kentucky warbler, hooded warbler, and yellow-breasted chat.

Bird migrations are strongly influenced by the presence of the Great Lakes. Waterbirds use the lakes and shorelines as flyways, and Michigan provides a unique opportunity to see a number of otherwise pelagic or Atlantic coastal species as they migrate from their breeding grounds to their oceanic wintering grounds. Hawks and other birds are concentrated by the shorelines of the lakes, as they avoid crossing the large bodies of water since lift is greater over land, allowing for more effortless soaring, and affording the bird watcher an opportunity to see thousands of these magnificent raptors.

Songbirds migrate mostly at night, but sites along the lakeshores often produce the best opportunities for observing large numbers of migrants. Bird watchers from the southern U.S. are often surprised to find out that by the time they reach Michigan, most of the breeding warblers, sparrows, and thrushes, are in full song as they near their breeding grounds, providing a wondrous dawn chorus on almost any morning in May.

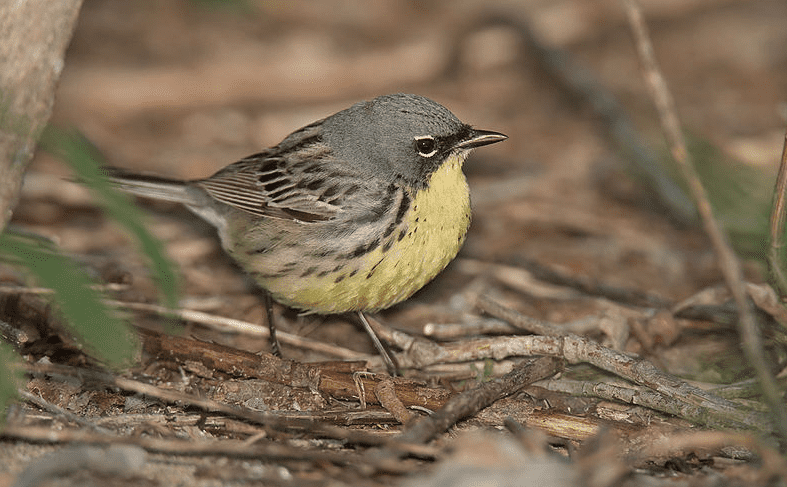

No introduction to bird watching in Michigan would be complete without mentioning our most unique bird, the endangered Kirtland’s warbler. The vast majority of the world population of Kirtland’s warblers breeds only in the north central Lower Peninsula of Michigan and migrates to the Bahamas for winter. This species is without doubt Michigan’s biggest drawing card for visiting bird watchers from around the world. Once here, bird watchers cannot help but notice the great diversity and beauty that Michigan’s birds have to offer.

A Brief History of Bird Watching in Michigan

The history of ornithology in Michigan is rich and extensive, with many regional and local works in addition to several important statewide publications. The first bird list for the entire state was published by Gibbs in 1879, although there were more localized listings published earlier, including a listing of birds in the Detroit region by Merriam in the 1700s. Merriam went on to explore the birds and mammals of the western United States. Gibbs’ list was followed by a more detailed account of Michigan’s birds by Cook in 1893.

This was followed by another thorough reference that updated the list of known species, published by Barrows in 1912. By this time, the last passenger pigeon had long since disappeared from Michigan, the only extinct species known to have occurred in the state. The work of Norman A. Wood, published in 1951, updated the state’s list once again, and incorporated a now growing body of data provided by increasing interest of the state’s birders, through 1943. By 1959, Zimmerman and Van Tyne published their distributional checklist of birds, again updating the state’s list. Payne thoroughly reviewed previous records and updated the state’s list once again in 1983.

The Michigan Bird Survey, a detailed accounting season-by-season of the state’s bird records, contributed by a growing band of birders, began in 1957. The survey was published in the state’s journal, the Jack-Pine Warbler from 1957–1989 and 1991–1993. From 1994–present, the survey has been published in the replacement journal Michigan Birds & Natural History. Much briefer versions of these surveys have been submitted for publication in North American Birds and its predecessors. From 1983–1988, Michigan’s birders took to the field in a monumental undertaking to document the breeding distribution of the state’s birds. The results were published in The Atlas of Breeding Birds of Michigan in 1991.

Currently, a second atlas is under way, which will run through 2006, which aims to document changes in breeding status and distributions from the first atlas. McPeek and Adams published another major work covering all of Michigan’s birds, titled Birds of Michigan in 1994. The Michigan Bird Records Committee was formed in 1988, and currently archives and evaluates records of casual and accidental species, as well as new species for the state list, and reviews these records to determine whether they should be published in the quarterly Michigan Bird Survey. The committee also regularly updates the list of accepted Michigan species.

More contemporary ornithologists have worked in Michigan. Among the more notable include George Wallace who, in 1961 discovered that an almost complete die-off of American robins on the Michigan State University campus was due to DDT being used to control Dutch elm disease. In 1955 he published An Introduction to Ornithology with Harold D. Mahan. Josselyn Van Tyne, among his many accomplishments, was the first ornithologist to show that North American birds returned to the same wintering areas in the tropics. In 1959, with Andrew J. Berger, he published Fundamentals of Ornithology, one of the first modern ornithology textbooks.

The Van Tyne Memorial Library, housed at the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology – Bird Division, where he was curator from 1931–1952, is named for him. In 1960 Harold F. Mayfield published a thorough life history of the Kirtland’s Warbler, simply titled The Kirtland’s Warbler. Mayfield is also responsible for developing a method for determining species nesting success and survivorship, now dubbed the Mayfield Method, which is extensively used in bird conservations studies worldwide. Lawrence H. Walkinshaw, a Michigan dentist with a passion for ornithology, is well known as a world authority on his favorite birds, the cranes.

In 1949 he published The Sandhill Crane, a life history of this species based largely on his 18 years of observations and research of the species throughout its range in North America and Cuba, including, of course, his home state of Michigan. In 1932 he became the first person to ever band a Kirtland’s Warbler, and his interest in the species resulted in his publication, The Kirtland’s Warbler: The Natural History of an Endangered Species, in 1983.