With a workweek behind me, I was excited to spend a Saturday with the birds and my camera! It was February, and bird photography in frigid weather has a unique set of challenges to overcome. For starters, dressing in warm layers and wearing warm gloves are essential.

As I was preparing to leave the house for a cold day of birding, I scoped out my backyard to see what bird action might be happening. To my surprise, there was a red-shouldered hawk perched on tree #16! (See my blog post about my backyard photography studio.) Grabbing my camera, I captured a few images of this first-time visitor to my backyard. Convinced this was a sign that it would be a great day of birding, I loaded up the car to get out there with the birds.

My first stop was the Ohio River Islands National Wildlife Refuge in nearby Williamstown, West Virginia. The feeders at the refuge were hopping with lots of species, including an abundance of my favorite sparrow, the white-throated. Just off the parking lot was a flock of robins, which are always a pleasure to see this time of year.

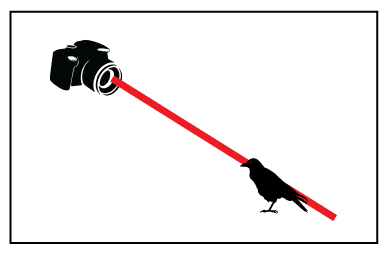

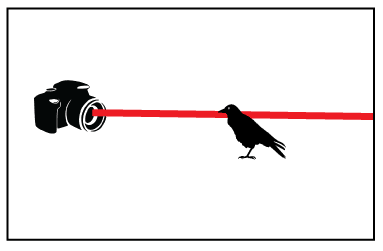

Tip #1: When photographing robins in a field or yard, make the bird stand out from the background by getting down low, at eye level with the birds. The birds’ background will be farther away, putting it in bokeh, yielding an image with a focus entirely on the birds. Who knew that there was geometry in photography? (See illustration.)

Later, while walking the refuge trails, I discovered a mockingbird that was very willing to pose for me as it sat in a thicket. The mockingbird was sitting among some lovely red leaves and briars.

Tip #2: The human eye is naturally attracted to the color red, and any time you have a chance to capture a nature image that includes a red component, it will catch the viewer’s eye.

My second stop was Newell’s Run, a waterfowl hotspot in the Ohio River’s backwater near Newport, Ohio. Upon arrival, a male and common female common merganser landed near me. As I pressed the shutter, I discovered in frustration and disappointment that my camera’s battery was dead.

Tip#3: On cold winter days, always have an extra fully charged battery or two handy, because cold weather will cause your camera battery to drain much faster than warmer weather. Keep your spare battery in a pocket on one of your inside layers to keep it warm.

I had a charged battery in my pocket, but by the time I loaded it in my camera, the mergansers were gone. However, I was able to grab a couple of images of a great blue heron wading for a snack.

It was time to move on to my next target destination. I headed for a remediated strip-mine area in Muskingum County, Ohio, where I’d heard reports of recent sightings of Lapland longspurs, a bird I’d never seen before.

When I arrived at the area, I found a string of slow-moving cars. I figured this must be the spot to see the longspurs. Then I noticed some familiar faces: birding friends in those vehicles who were also looking for the longspurs! They were communicating on two-way radios, and since I also had walkie-talkie in my car, we agreed to radio one another if we found the birds. The birders parted company, and while driving around the vast, open area, I spotted American kestrels, eastern meadowlarks, and rough-legged hawks. We encountered many American tree sparrows feeding on the ground, which raised our hopes, thinking they were ground-feeding longspurs.

Soon the call came over the radio from one of my birding pals that they had four Lapland longspurs right in front of them. Receiving the location, I quickly made my way there. I approached the area slowly to not flush the birds. As I exited my car, I realized that I was looking into the sun to see the birds. Knowing this would never work for a photograph, I made a wide route on foot around the birds to get the sun at my back.

Tip #4: Don’t walk directly toward birds you hope to photograph, and approach only if the birds seem not to be alarmed with your presence. As you slowly approach, take a few shots so they become familiar with the sound of your camera, and realize that it is not a threat. (For more information about approaching birds to photograph without disturbing them, be sure to read my upcoming article in the July/August 2021 issue of BWD.)

I was standing on the centerline of the road, and the birds were in the grass just two feet off the road, so I would guess I was within ten feet of them! This is a rare occurrence with longspurs, and was a real thrill. After firing off a few images and doing a subdued version of my life-bird dance in the middle of the road, I returned to my car, having experienced my first lifer of 2021, a species that breeds in the Arctic tundra.

We were not far from a favorite location of mine, where I have photographed short-eared owls many times, so I decided to stick around, hoping to photograph them. After capturing a couple of images of some shorties, it was time to head home. It had been a great day for winter bird photography.