Late one December I found myself among a loose aggregation of birders standing by a roadside in Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware. To our north stretched a field, and somewhere in it there was supposed to be a northern lapwing, a handsome Eurasian shorebird that always makes news when it appears on our shores.

After a bit of waiting, we briefly saw the lapwing fly by on its odd, paddle-shaped wings. It landed out of view in a low spot, and all of the assembled birders headed out along the field edge in hope of a better look. As we walked along, a dark bird appeared in the distance and beat its way toward us.

Though far away, the bird was obviously large. Very large, maybe even huge. The long wings flapped with unmistakable power, quickly halving the bird’s distance to us. A man and woman who were walking more or less beside me stopped nearby, and all three of us examined the oncoming bird, the lapwing momentarily forgotten.

Though the dark bird was flying quite low, the light was dim, and it was not easy to discern detail against the sky. But it was still apparent to me that we were looking at a juvenile bald eagle, and that if it continued on its present course, we were going to have a thrillingly close encounter with it.

That is exactly what happened. The eagle passed right over our heads, close enough that one might almost have felt the rush of air off its wings. I turned to my neighbors, wanting to somehow acknowledge the experience we had just been fortunate enough to share.

But instead of returning my contented gaze and wide smile, they were looking at each other with faces that betrayed puzzlement, not elation. Instantly, I knew that they were unsure of what the bird was—an unsettling emotional state in which I’ve spent far too much time myself.

Finally, the man spoke sotto voce, cocking an eyebrow at his companion, “TV . . . or BV?” She shrugged helplessly, saying nothing, and silently they headed on toward the spot where the lapwing had disappeared.

My heart didn’t exactly sink, but it briefly took on a bit of water. These people had just had an eagle zoom right over them, but they hadn’t fully enjoyed it because they were unable to recognize it as such. Instead they were trying to make their observations fit their mental image of turkey vulture or black vulture, and it wasn’t working.

I considered telling them what they had missed, but many of you will know what stopped me—a feeling that I would only be making a small private humiliation both larger and public. I love to teach, but you have to pick your moments.

The story ends happily, though, as we all soon enjoyed wonderful views of the lapwing. I’d wager that the couple have completely forgotten the big dark bird that left them scratching their heads, but I have not. And so, picking my moment, I’d like to offer a few pointers on bald eagle identification.

To begin with, the two birders would have had no trouble had our eagle been an adult. Though a lot of birders struggle with identifications of all sorts, very few people hesitate to call an adult bald eagle just that, provided it was even reasonably close by.

But the very distinctiveness of mature bald eagles sets a trap into which far too many birders fall—the root problem that keeps so many birders from coming to really know bald eagles is that the adults are just so darn distinctive.

Most everyone, if asked how to identify a bald eagle, could at least stammer out a few words that, reduced to the simplest terms might be stated as follows, “big + brown + white head + white tail = bald eagle.” This white head-white tail algorithm is so firmly entrenched that you’ll frequently see people trying to force other birds into it—great black-backed gull and osprey leap to mind.

The basic equation isn’t false, but stopping there is a little like saying, “ham + eggs + white toast + black coffee = breakfast.” Sure, that’s a breakfast, perhaps you even think it’s the ideal one, but wouldn’t it be nice to have blueberry pancakes every now and again? How about some fresh-squeezed orange juice?

If you limit yourself to only the most basic field marks and recognizable plumages, you may not starve, but you’ll be missing out on a lot of great stuff. Careful, though. Once you let go of the idea that all bald eagles have white heads and tails, you’re going to go through a period of discomfort, when you’ll suspect that nearly any big dark bird might fit into your newly expanded definition. You may at times feel that you no longer know what any bald eagle looks like.

After all, when you begin to include all the possible plumages, you find that bald eagles may show dark heads with dark bellies, white heads with dark bellies, or dark heads with white bellies. Their tails can be dark, white, or some of each.

You may briefly flirt with the idea of abandoning birding in favor of something less complicated and more easily grasped—particle physics, for example. Such thoughts are just growing pains and will pass, leaving you with a richer, more nuanced understanding of the species.

Plumage in Four Parts

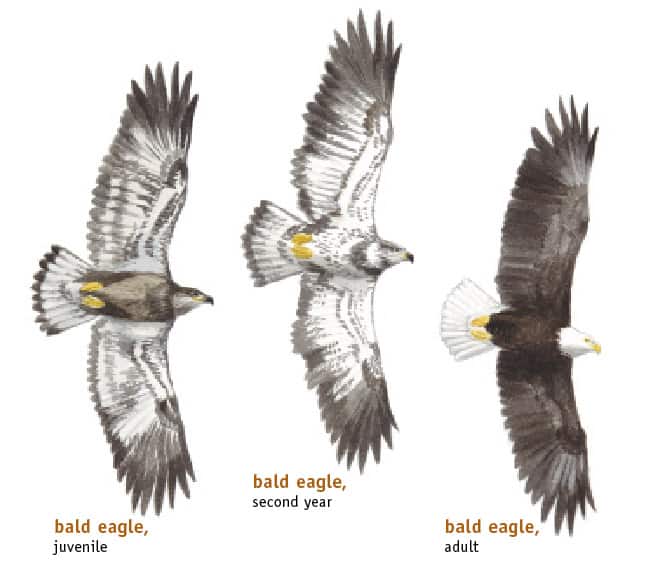

Let’s take a closer look at those plumages and divide them into four categories. Adult plumage, which everyone recognizes, is attained in the fourth year of a bald eagle’s life and replaced by identical feathers from then on. Juvenal plumage, worn for a bird’s first year, is characterized by a dark brown head and body, though near the end of this time, the belly may fade to a paler brown. Years two and three are probably the hardest to get a feel for, but painted in broad strokes, here’s how it goes.

Remember that we are going from a dark headed, dark-bellied bird in year one to a white-headed, dark-bellied bird in year four. In year two, the belly is mostly whitish flecked with brown, but the entire head and breast are still dark, giving the bird a hooded look. In year three, the head whitens and the belly darkens. Early on in this year, bald eagle bellies will be predominantly white with brown flecks, but the brown will win out, replacing most or all of the white. The face, crown, nape, and throat will go from mostly brown to mostly white.

As the head whitens there often remains a dark brown eyestripe. At first, this brown lends the bird a heavily masked Ninja or bandit look. Later on it can thin, creating a faux osprey face. Of course, you mostly see these facial details on perched birds.

If you do get a perched bird, or a low-flying one, you might also look for beak and eye color, which both go from dark to yellow as an eagle moves through its first four years.

The Tail’s Details

You may be wondering why tails haven’t been discussed yet. The reason is that they are quite variable and are often not a good indication of a bald eagle’s age. They can be anywhere from dark with some whitish mottling (as they often are on juveniles) to pure white (as they typically are on adults). In between, the tail usually shows a white to whitish base, with a variably thick dark terminal band across the tip.

Some balds have tails that are very like those of a golden eagle in pattern, though not in length. Balds are always proportionately short-tailed and large-headed, whereas goldens have long tails and small heads.

Balds versus Goldens

Speaking of golden eagles, I think birders generally overestimate the difficulty of telling them apart from balds, mainly because their common names both contain the e-word. In this case, “eagle” simply means “big raptor,” because the two are not closely related in a taxonomic sense.

The previously mentioned differences in head and tail proportions are usually the best marks to use on distant flying birds. If you get a flying eagle close-up, the first thing to look at are the axillaries—the feathers on the underside of the wings where they join the body—otherwise known as the “wingpits.” I have never seen a bald eagle young enough to still have a brown head that didn’t also have white or whitish axillaries. And I’ve never seen a golden eagle of any age that didn’t have solidly dark wingpits.

Naturally, if you have an eagle-sized bird with dark wingpits and a white or whitish head, it will be a bald. But only if you are seeing the head color correctly. Occasionally a golden eagle at some distance may appear to be white headed, especially if it has a lot of the gold feathers on the neck from which it takes its name.

Let’s go back to the question of the lapwing field, “TV . . . or BV?” Although it’s true that many people confuse our two eagles with black and turkey vultures, the only pair to choose between is turkey vulture and golden eagle. Both have long-tailed, small-headed silhouettes, and they share a habit of soaring in a dihedral posture, with wings raised a bit above the flat horizontal. What you will not see either golden or bald eagle doing is teetering from side to side as turkey vultures so often do. Turkey vultures “rock.” Black vultures have a short tail, but their small size and snappy, frequent flapping make them fairly unlike either eagle.

Shape

Especially when attempting to identify flying raptors, shape is among the very first things one should assess. Shape is important and useful on bald eagles, too, but there is a pitfall here.

One thing that’s great about shape as a field mark is that it tends not to change much in birds, despite differences in age and sex, whereas plumages vary drastically. But many birds actually do change their shape somewhat as they move from juvenile to adult. With most small birds, and many large ones, these differences are slight.

Raptors are an exception. Quite a few of them do alter their shape perceptibly over the first year or so of life, and bald eagles are a good species for demonstrating the phenomenon.

A juvenile bald eagle has wings that are considerably wider and blunter than those of an adult. Look at a good photograph or painting of a first-year bald eagle in flight, and you will see that it looks a bit like a flying door. The secondaries are quite long and the wingtips blunt. An adult bald eagle calls to mind something more like a flying board, perhaps a snowboard, though that last image overstates the roundness of the wingtips considerably. But it looks a good deal more aerodynamic and less hulking.

The tails of juveniles are also longer, which means their shape is a bit more like golden eagles. Balds still have those big heads that project well out past their wings, and even the longest-tailed bald looks stubbier than any golden.

If you happen to see a second-year bald eagle—the ones with mostly white bellies and dark bibbed heads—look carefully at the trailing edge of the wings; they will often appear ragged and uneven, as the longer secondaries of the first year are replaced by shorter ones. The tail may show a similar unevenness.

If bald eagles are infrequently seen in your area, you can look for the shape difference between juvenile and adult red-tailed hawks. Like bald eagles, the young birds have longer tails than adults. The difference in the wings is reversed, though, with the juveniles having narrower wings than their elders.

Why would such differences in shape occur at all? One plausible explanation says that the shapes of juveniles give them more leeway for less skillful flying, whereas the adults have a more high-performance structure that allows for greater maneuverability but is harder to control.

I once heard a bird identification expert discussing how it felt to study identification. “At first, you think you’ve got it pretty well figured out,” he said, “But then you look at it some more, and it starts to seem confusing again. Then you reach another place where you think that this time, you really understand it, until you suddenly realize that things are a lot more complicated than you ever suspected. And so on . . . ”

Wherever you are in your study of bald eagles, I urge you to go out and punch through to that next level. Even if some of the progress you make is later revealed to be partially incorrect, you’ll still be a better birder for it.