When bird watchers die (or, as my dad would say, shoot through), they must go to North Dakota in June. Heaven just wouldn’t measure up. Consider: It’s beautiful, waving with grasses, studded with countless wetlands, overarched by majestic skyscapes. It’s crammed seemingly past capacity with birds, many hard to see elsewhere, all breeding.

The air vibrates with the joyous burble of western meadowlarks and the eerie ululations of winnowing snipe. The roads are perfectly straight, the corners square, so it’s hard to get lost. There’s nobody else around, so you can crawl along at 10 miles per hour, casting your glance across the landscape, and pull over in a heartbeat when a ferruginous hawk sails into view.

It stays light until 10:30 at night, low, buttery light bathing ducks and shorebirds in gold. And almost every little town has a terrific roadside café, sweetly fragrant with fresh coffee and homemade pies. Could a birder ask for anything more?

Let me paint another picture. You stop your car in front of a little pothole, maybe the size of your front yard. There are eight species of ducks floating around, some trailed by peeping broods of ducklings. Pintail, blue and green-winged teal, shoveler, mallard, lesser scaup, gadwall, and ruddy ducks. Or canvashacks, redheads, ringnecks.

Take your choice. Wilson’s phalaropes spin and pick at the water’s surface; black terns, in colors of cast iron and pewter, dip and dive for minnows. Western and eastern kingbirds sit side-by-side on a low wire fence. Red-winged and yellow-headed blackbirds konk and bray on the fringes.

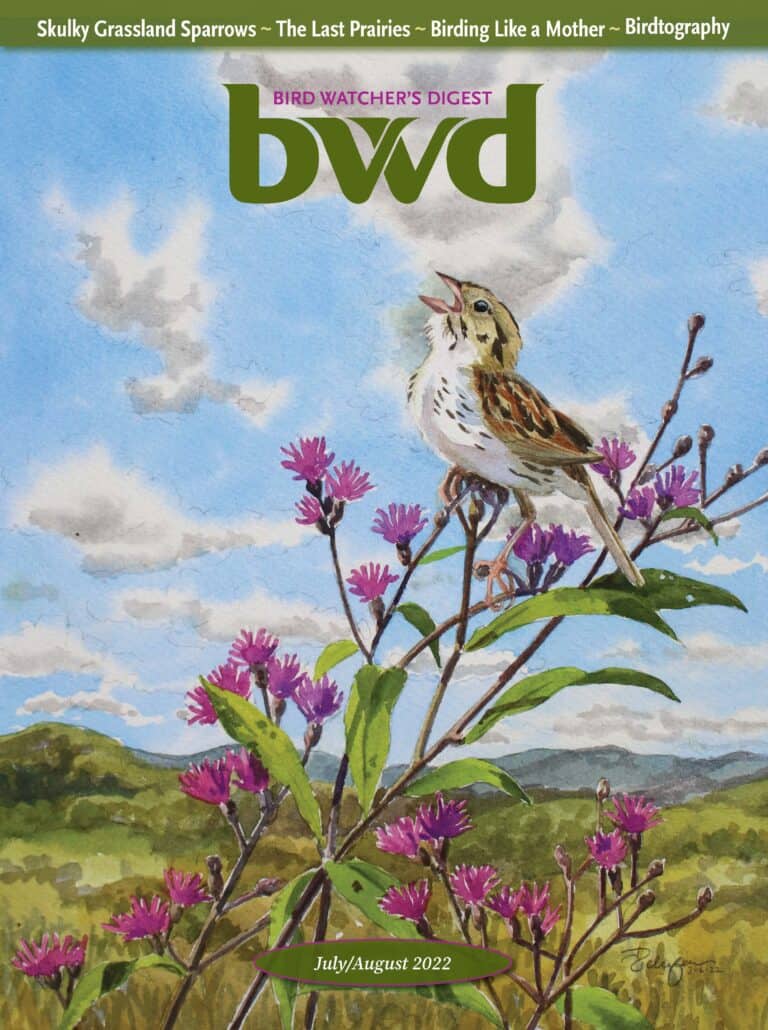

All around, grasshopper, vesper, and Savannah sparrows lisp and buzz. Bobolinks broadcast their shortwave bird radio. You step out of your car to take it all in, and an American avocet streaks toward you, complaining, as its apricot-fuzzed chicks hurry into the cattails.

In an all-out effort to bring its incredible wealth of birds to greater prominence, a group of volunteer birders and business-people from the prairie pothole region of central North Dakota formed Birding Drives Dakota. The communities of Jamestown, Carrington, and Steele anchor the driving routes, which incorporate pastureland, seeded and virgin prairie, and innumerable lakes and wetlands, small and large.

These communities cooperated with the state and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to launch the first Potholes and Prairie Festival on the weekend of June 13, 2003. Around 300 people—mostly North Dakotans, with a smattering of attendees from Minnesota and South Dakota—flocked to the festival, far exceeding organizers’ expectations.

My husband Bill and I were asked to provide some seminars and evening entertainment. We leapt at the chance to visit. Had we had any idea what bliss awaited us, we’d never have waited to be asked.

Bill and I rented a car at the Fargo/Moorhead airport and headed west. On the deserted gravel roads, crawling from pothole to pothole, when our speed hit 10 miles per hour, all the doors would automatically lock with a loud, startling zzziiiiich, which soon proved annoying, because our birding speed averaged around 15 miles per hour, and we stopped dozens of times a day.

The Mercury seemed to want to thwart us, and was always shrilling and admonishing. Driving through the tiny hamlet of Gackle, North Dakota, we decided to borrow its name for our imperious, noisy car. Gackle. It seemed to fit.

Central North Dakota boasts the Missouri Coteau region (French for hill), which bears the beautiful scars of an ancient glacier. For refugees from unglaciated southern Ohio, where the few lakes we have are human-made, the Cocteau is a vision of paradise. Every gravel road holds a different geological surprise—high ridges or conical eskers and drumlins—gravel deposits left by the receding ice sheet, now clothed in soil and soft, waving prairie grasses and wildflowers.

Unexpected secret gardens hide beneath the grass tops—wooly blue squawroot, cheery gaillardia, purple peas and vetches, scarlet globe mallow, white penstemon and anemone, blue harebell. Purple prairie smoke wafts its feathery seed heads on stiff stems.

Tiny Mammilaria cacti open umbrellas of fragrant orchid-pink flowers, three to a plant. Silvery and Melissa blue butterflies, inornate ringlets, bronze coppers, and monarchs dance low over the flowers. The two constants in the ever-changing landscape are grass and water—water everywhere, in pools, potholes, and large, shallow lakes.

Wet summers for the past decade have brought many lakes outside their traditional banks, and stands of drowned cottonwoods provide ideal nesting platforms for double-crested cormorants and black-crowned night-herons, whose populations are expanding in the region.

Every single pothole, no matter how small, has birds on it: pied-billed eared and western grebes, a dozen species of ducks, Wilson’s phalarope, marbled godwit, willet, snipe, American avocets, white pelicans. One of the world’s largest nesting colonies of white pelicans, more than 16,000 pairs, stinks up Chase Lake National Wildlife Refuge, and the majestic birds are almost always visible overhead, spiraling in stately squadrons against towering clouds.

Musing on why I was in a state of suspended rapture for the five days we were in the Coteau, I realized that any of the species listed here would cause me to slam on my brakes at home in Ohio. Not only that, but the region holds some true specialties, birds that make holes on most birders’ life lists.

However you feel about sparrows, arriving in a region that harbors 18 species will endear them to you. It’s a delight to become conversant with the songs and habits of species like vesper, grasshopper, clay-colored, and Savannah spar rows.

They sing on wires and fenceposts, exhibits A through D in Sparrows 101. But the real treasures are harder to come by. Le Conte’s, Nelson’s, and Baird’s sparrows are the three limited-range, “gotta have” species in the Coteau. Though we were told that in some years, Le Conte’s are “everywhere,” we were skunked.

On the last day of the festival we still hadn’t seen the other two, either. Bill was beginning for the first time to feel a little glum. We were on our way to the festival’s farewell picnic luncheon at Chase Lake NWR when we encountered Steve Gross, a delightful, soft-spoken retired Air Force colonel and BWD subscriber who was seeking Baird’s sparrow for his eye-popping North American life list, more than 100 species longer than mine.

He’d been told by a local birder that the shortgrass hilltops near Chase Lake’s refuge sign were a good bet. We thanked him for the information and went on. Coming to the third cattle guard, we pulled off and hopped out to listen. A strange sparrow song—soft and musical, with four introductory notes and a slow trill, sifted over the hill. I didn’t know what it was, but I knew I’d never heard it before.

It was time to find this bird. I took off at a lope through the grass. In the distance, we could see Steve’s car, and I saw him focus his binoculars on me. I gave him the thumbs-up and he started walking toward us.

Single-minded doesn’t quite describe us on the quest for a life bird. I was completely oblivious to the fact that Prairie Public Television had pulled up in a white van to film Bill and me as we birded. Trailed by Bill, who was carrying the spotting scope and answering rapid-fire questions from an interviewer, a camera man, and a soundman with a large boom microphone, Steve and I headed 100, 200, 300 yards into the prairie, without coming much closer to the mystery sparrow’s song.

Finally it seemed to be singing from underfoot. Now what? We strained our eyes into the vegetation looking like dogs on point, wondering if our singer would ever pop up. And it did, at long last, a small, streak-breasted, pale sparrow, singing happily, unconcerned about the odd-looking people and equipment focused on it.

Over the next hour and a half it was to circle its territory many times, always fetching up on one small legume that protruded enough from cover so we could observe it. The television crew wandered away, and Steve, Bill, and I were alone with the sparrow and the sun and the soft, fragrant air. It just doesn’t get any better than that. And it was all on film!

Taking fond leave of Steve, we retired to the nearby festival luncheon. I left my sketchbook open, not too subtly, to a sketch of a Baird’s sparrow, which none of the festival participants had yet found. Soon we had a large charter bus full of excited people hoping to add it to their life lists. too.

The heat was on! We led the bus to the spot, found our trail through the grass, and 20 people snaked single-file to the spot where we’d found the bird. And, unbelievably, there it was, singing on its silvery perch, as happy and oblivious to the fuss as it had been three hours earlier. This bird, which may never have seen a human being in its life, now saw 22, and every one of them wore a broad smile. Happiest of all was Bill, who loves nothing better than showing new birds to nice people.

Monday came, and our flight out of Fargo wasn’t until 4 p.m. We rose with the sun and headed back to the Coteau. Horsehead Lake produced Franklin’s gulls, Forster’s terns, marbled godwits, white-rumped and pectoral sandpipers, semipalmated plovers, and two unexpected bonuses: a lovely drake cinnamon teal and a piping plover. We watched snipe winnowing overhead, tilting in flight to let the air from their beating wings eddy through widely spread outer tail feathers. This makes a strange bleating woo-woo-woo-woo-woo that we had heard dozens of times without being able to connect it to an individual bird. Usually, it’s done at such great heights that the bird simply can’t be seen: hence the term, “snipe hunt!”

I have to admit that Bill is the more avid lister of the two of us. He also has the better birding gear. I tend to bliss out, doodling along watching ducks and shorebirds without worrying about holes in my life list. He’s more focused, and I owe him many a life bird. (He also carries the scope. Life is good.) Now he was after Nelson’s sparrow. He’d asked around, and was told that black-grass sedges were the preferred habitat. We found a likely looking marsh and settled in to listen for the Nelson’s sparrow’s undistinguished hissing song.

Bill was wearing a pair of field pants that zip off at the knee. It was hot, so he unzipped the legs, and took his shirt off for good measure. I turned from the scope to see a changed man. “I thought I’d take a little sun so I won’t go back home looking like a slug,” he explained. Suddenly we heard a likely hiss from deep in the marsh. I plunged into the sedges and headed for the song. Realizing that I might flush the bird first if he didn’t come along, Bill grabbed the scope (see a pattern here?) and lugged it through the barbed-wire fence.

Sure enough, two small sparrows popped up out of the marsh, gave us a distant, two-second view, and dropped back into cover. At that moment the mosquitoes found us, or more properly, found Bill. Large expanses of unprotected, tender white flesh, deliciously fur-free, were exposed for the piercing.

He was covered by a whining horde. Slapping frantically while trying to balance the scope and binoculars, we chased the popping Nelson’s sparrows, catching a glimpse of a bill, a cheek patch, a shoulder stripe, finally adding it all up to a life species.

By the time we’d made the ID, we were laughing and wailing, cussing, and flailing. I hooked my pants on a barbed-wire fence, got stuck, was instantly covered with mosquitoes, panicked, almost dropped the scope, and ripped a big hole in my best khakis. Bill, wishing he had pants to rip, staggered out of the marsh, a pint low on blood. Little wonder that sparrow species is so recently described and so rarely seen. We piled back into Gackle and were for once happy to hear the doors lock behind us.

The prairie was to yield up some life mammals for us, too. Searching for sparrows. Bill tracked some high-pitched whistles to a black-tailed prairie dog town. Watching the sod poodles playing and grooming each other, I couldn’t believe that exotic pet dealers vacuum them from their burrows and consign them to dreary, small cages, like overgrown guinea pigs. Perhaps monkeypox and bubonic plague, which they can carry and transmit to humans, will in the end be their saviors.

On our first morning we were scanning a farm pond for shorebirds when a large cat walked out of a grove and sat, facing us and the sun. I studied it through my binoculars, then through the scope. Its face was broad, its jaw heavy, its shoulders burly beneath a thick neck. “I think I’ve got a bobcat here, dear,” I said. Bill raised his binoculars. “That’s a house cat, sweetie,” he said, and went back to watching birds. I smiled and waited. Sooner or later; the cat would get up, and I would have an answer. Maybe I was wrong.

The cat got up, stretched, and padded along the pond shore. Round spots marked its gray-brown flanks. A half-tail, ringed with black, switched behind it. It was thickset, powerfully muscled, and it was the size of a springer spaniel. I began to crow and do a little dance. When I’m excited, I sing nonsense songs. “It’s a bobcat, just look through the scope, it’s got half a tail and spots, oh, it’s a bobcat, it’s a bobcat, it’s a big ol’ bobcat…” Bill leapt to the scope and drew in his breath. “Wow! That thing is huge! Look at that tail!” He believed. A life mammal for him, in exchange for the prairie dogs he found for me.

In roadside cafés Bill and I would tally up the species we’d observed, and were ourselves observed by native North Dakotans. They’re a kind lot, but not overly conversational. They’ll stop to ask if you need directions, and they are bemused by us, who take such an interest in the diverse and abundant avifauna they take mostly for granted. Although they’re pleased and amazed that we’d come all this way just to see some sparrows, and appreciate that it could boost the tourism economy, some were just a little bit concerned that it could get out of hand.

North Dakotans like their lonely vistas and abandoned homesteads, with barn swallows darting in and out of empty windows. They endure the long, dark winters, only to fall in love with the prairie all over again come spring. Loneliness is part of what they love about their land.

Several years ago, sound recordist Lang Elliott asked me to draw a pothole scene for the liner notes of his bird song CD Prairie Spring. As he read out the list of birds and habitat types he wanted me to include in a single drawing for the folding liner, I stopped him. “Would it really be possible to see all these species together? Don’t you think this is overkill?”

He laughed. “Not at all. If anything, we don’t have enough birds in there.” I had to take his word for it and dutifully executed a crowded, busy marsh, popping with ducks, shorebirds, and songbirds, sharp-tailed grouse lekking in the distance. Now I know what Lang was describing, because I’ve experienced it.

There is a birding heaven. We’ve been there and come back to tell about it. Central North Dakota is not the first, or even the hundredth, place that springs to mind when people plan vacations. It’s not Cancun, or the Vineyard, or Orlando. It’s not flashy or trendy, or even remotely geared to the urbane sophisticate.

What it offers is breathtaking beauty, or serenity, and a wide-open remoteness that frees the soul. In late spring it’s absolutely alive with breeding birds and animals. They know where to go to be left alone. North Dakota is not on the way to anywhere. It’s as much a state of mind as a state, and you’ve got to want to go there, seek it out, and settle into it, like a meditation. Ommmmm. Keep the coffee on and save a piece of coconut cream pie for me. I’m coming back.

Looking to Subscribe?

Get 6 print issues of the magazine delivered to your door & free digital access

One Year Print Subscription: $26

(to US or Canada, includes digital access)

One Year Digital-only Subscription: $15