Why not go for it? So it’s late in the season; so what? Let’s see if you can do it even in the heat of August. If you can get to Cimarron County and Black Mesa country with enough daylight, there is no telling what you can see! So why not try for it?

With those thoughts I exhorted myself upon awakening early on an August 6th morning in a motel at Newkirk, north of Ponca City, in north-central Oklahoma “It,” the objective that I could hardly arouse sufficient confidence to pursue, was a “Century Day,” i.e., a 100 species-or-more bird list for that hot August day. I had succumbed only a few days earlier to the Big Day challenge, that “lure of the list” indigenous to the prime time of spring migration. I’d not previously considered such a project for any months other than April or May, certainly not for August.

On the day before, I had driven solo nearly 600 miles west from Oxford, Mississipi; I was headed eventually for the Denver area. I managed to reach north-central Oklahoma in time to traverse a back road between Grainola and Newkirk, on the long-shot possibility of encountering the greater prairie chicken in the last hour before sunset. Shortly after sundown I received some reward for my efforts—I didn’t see the chickens, but I did hear the plaintive whistles of upland sandpipers flying overhead. As their calls drifted down to me from the darkening sky, I wondered if they were early migrants already setting their southbound course for the pampas of South America.

Now it was the next morning, and I had decided to make a Big Day run from north-central Oklahoma clear across the Panhandle to its northwesternmost extreme. I started The Big Day clock at 7:10 a.m. as I headed for the Arkansas River crossing, seven miles east. A dozen common roadside species were seen and/or heard along the way before I reached the riparian woodland at the Arkansas; the area quickly yielded eight more species.

Necessitated by the construction of Kaw Dam about ten miles downstream, there was a good view of the narrow, shallow stream flowing in a small portion of the broad channel. Such is the typical condition for all larger streams running west to east across Oklahoma at most times of the year, except soon after exceptional rains. Some still pools away from the flow in this extreme backwater of what was now the Kaw Lake basin provided habitat for several great egrets as well as green-backed, little blue, and great blue herons. Even better—on a sandbar near the river’s edge—was a single piping plover, always a rare species in Oklahoma and the best bird of this day. The time spent carefully confirming this sighting was doubly fruitful as a pair of wood ducks flew past and as the ringing call of a pileated woodpecker trumpeted its presence, a species I hadn’t expected.

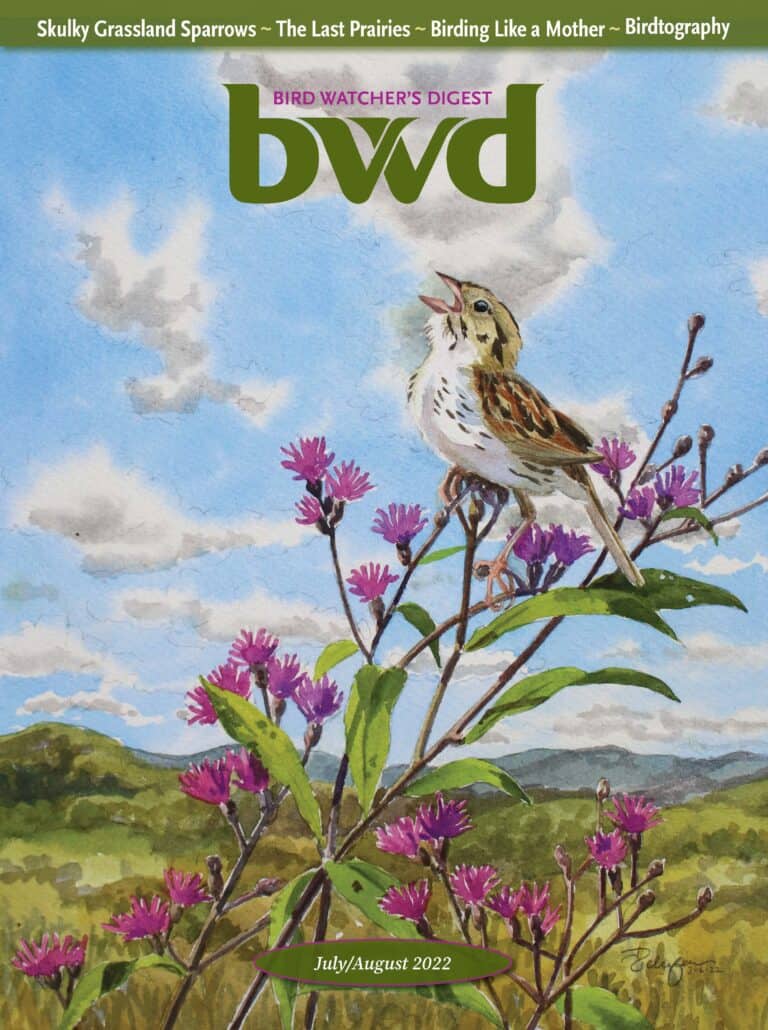

Driving another mile eastward before returning to Newkirk, I found ten more open-country birds, including the unobtrusive, easily overlooked grasshopper sparrow on a fencewire, and the oft-singing, obstrusive, and not-easily-overlooked dickcissels, on the utility wires. Departing from Newkirk at 8:40 my count was a mere 42 species. I knew that with no stronger a beginning than this it would be an uphill climb to reach or pass 100 species. And I was later to wonder if I should have spent a bit more of the cool of the morning searching the banks of the Arkansas River.

Indeed, the day did become an uphill climb figuratively, as well as a literal uphill climb of 3,400 feet, from a lowest elevation of about 1,140 feet above sea level at the river to an elevation of about 4,500 feet at the highest point I was to reach in northwestern Cimarron County late that day.

Traversing an arrow-straight, 61-mile stretch of state highway (OK 11), I stopped only for large flocks of cattle egrets in grassy fields and for two black-crowned night herons at a marshy spot. Western kingbirds on roadside perches took no viewing time. Breaking my westward trek, I birded the Salt Plains National Wildlife Refuge. A large flock of great-tailed grackles fed in a refuge field. Eagle Roost Nature Trail seemed promising for birds of woodlands, as well as for water birds, shorebirds, and waders, but the woods were empty, and I added only a Mississippi kite, a red-headed woodpecker, and a tufted titmouse. Sand Creek Bay produced numerous American avocets, snowy egrets, non-breeding white pelicans, several local-breeding least terns, greater yellowlegs, a flock of eleven ring-billed gulls and on Franklin’s gull.

Despite my 10:00 am arrival, the discomfort index was already miserably high, from both temperature and humidity. By 12:15 p.m. I felt compelled to depart, because of the oppressiveness at 92 degrees with no breeze. Down the highway I sped, with only 60 species, fervently giving thanks for auto air conditioning. It was still 250 miles to Boise City, Oklahoma, in Cimarron County.

After another 99 miles, an unrewarding stop at Doby Springs Park, and still a few miles short of the panhandle’s beginning, I jogged south through Laverne (population 1,563), passing under the main street sign still marking it as the “Home of Jane Jayroe, Miss America of 1964.” Also noteworthy, the time and temperature sign read 99 degrees at 2:22 p.m. Entering the panhandle on OK 3, I soon saw another striking road sign. This one pointed the way north to the Beaver County seat of Beaver (population 1,939), touting it as “The Cow Chip Capital of the World!” It is remarkable wherein some small towns find their distinctions.

Another arrow-straight 60-plus miles brought few birds and no new ones. In Texas County, the second of the three composing the Panhandle, I couldn’t resist the temptation to detour for what proved a fruitless stop at Optima Lake, another Corps of Engineers reservoir. But shortly beyond that turnoff, a large playa visible from the highway proved to be a hot spot yielding 12 new species: mallard, northern pintail, northern shoveler, blue winged teal, 30 early-migrating white-faced ibises, American coots, solitary and least sandpipers, a lesser yellowlegs and long-billed dowitcher, black terns flying over, and a few yellow-headed blackbirds in the surrounding cattail marsh. This array of birds exemplified the August concentrations of breeding and migrant water birds found wherever water is available in the parched plains.

At 4:50 p.m. I arrived at Guymon, the major city of the Oklahoma panhandle (population 8,492) where a temperature sign proclaimed, correctly or not, 106 (dry) degrees! A gasoline/quick-stop cashier assured me that the thermometer “reads three or four degrees high.” Either way, no inducement to linger here! At this point the land had already risen nearly 2,000 feet from my lowest starting elevation at the Arkansas River, and another 1,000-feet rise still lay ahead. In the next 50-plus monotonous miles, the only relief was the sight of a few lark buntings on roadside wires, for species 76. With 24 more needed to reach the century mark, I began to realize that my species total might not climb as high as the day’s temperature.

At last Boise City (population 1,761) was near; I turned off to go directly to the town’s sewage lagoons—the only permanent water for many miles around, and thus another bird magnet. I quickly mined this spot for ten new species—ducks, shorebirds, and swallows—to reach 86 by 7:30 p.m. At the prairie dog town six miles north there were the expected burrowing owls plus an unexpected feruginous hawk (as well as Swainson’s hawk, which wasn’t new). Along the highway westward from Boise City toward Black Mesa State Park, a common nighthawk was added as it fluttered over slightly rolling sand sage-yucca grasslands.

Beyond the route of the Old Santa Fe Trail, in the valley of South Carrizo Creek, I drove toward a state park and Lake Carl Etling. The creek bottom supports considerable low willow growth and some moderate-sized cottonwoods. Here I was able to quickly tally the blue grosbeak, yellow warbler, and northern flicker; along the rocky slopes were several brown towhees, and a surprising female Brewer’s blackbird walked confidently around an open grassy area, bringing the species total rapidly to 94! How my confidence rose with it!

Driving up a side canyon to the higher ground at the west, I stopped short of the top for birds in the low scrubby oak growth—they proved to be a pair of rufous-crowned sparrows. Turning back to the auto, I found behind me posed against the western sky a roadrunner whose curiosity was aroused by my squeaking for the sparrows.

Over the ridge and down into the next valley west of the park I drove on a dirt road. Abruptly I stopped for a group of gray birds in the road, most of which were merely mourning doves; but among them was one female scaled quail! While taking in this sight, I heard the calls of a curve-billed thrasher, and then spotted it in the top of a large cholla cactus. The birds were becoming accommodating.

Back on the paved road from Boise City to Kenton (and into New Mexico), I headed east toward the turnoff for Watson’s Crossing of the Cimarron River. En route, an American kestrel became species 99. The sun had slipped behind Black Mesa and the lesser mesas to the west as I pulled off the dirt road 100 yards short of the one-lane concrete low-water crossing of the river channel. Where the open shortgrass-yucca pastureland meets the salt cedars, willows, and cottonwoods of the river flood plain, I heard the buzzy call notes of three Bewick’s wrens, who yielded to my coaxing to show themselves. Species Number 100! But at the same moment, the calls of a Cassin’s kingbird, unseen in the canopy of a tall cottonwood, became discernible among the calls of the more abundant western kingbirds giving their dusk chorus. By 9:10 p.m. I had exceeded my goal after 432 miles and 14 hours.

But there was too much light left in the sky to quit. (After all, I was as far west as the Mountain Time Zone, six miles northward in Colorado.) Also, I had yet another goal besides the daily total. Taking my cassette tape-player in hand, I walked to the “bridge” and onto the riverbed. As at most other times, one could step across the trickle comprising the Cimarron River.

Walking downstream, I began to play the calls of the western screech owl. My timing was excellent, for within one minute of play, I received an answer from the distance. Soon, pairs could be heard in duet-calling on both the south and north banks of the river. This accomplished my other goal, being my first-for-state as well as only second-for-life record of this recently split species.

Into the bottomland woods I followed the calls of one pair. Before reaching them, while using a spotted owl call on my tape, I provoked alarm notes from three additional new species for the day—the American robin, northern mockingbird, and brown thrasher—to reach a final total of 105 species. Moreover, the owls cooperated well as one showed itself in flight and another remained perched in my flashlight beam for good viewing only 15 feet above me.

Slowly and reluctantly, I left behind the two pairs of owls, both still giving the duets of their “bouncing-ball” calls, the only sounds in the stillness. What a great finish to an exhilarating day of birding, as darkness settled over the Cimarron Valley and the Black Mesa country of westernmost Oklahoma.

Looking to Subscribe?

Get 6 print issues of the magazine delivered to your door & free digital access

One Year Print Subscription: $26

(to US or Canada, includes digital access)

One Year Digital-only Subscription: $15