We put our raft in on the Upper Marsh Fork River under cloudy skies cloaking the 9,000-foot limestone peaks of the 700-mile-long Brooks Range in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) in northern Alaska. The bush plane that dropped us off with 400 pounds of gear left us on a field of dewy tundra for a bird-watching excursion that spanned from the North Slope of the Brooks Range to the frigid Arctic Ocean.

Immediately, a golden eagle soared overhead as three companions and I busily organized gear into dry bags for our 2-week, 160-mile birding adventure. Beginning in the Upper Marsh Fork, we eventually converged with the Canning and then the Staines River before reaching the ocean. We left in early July, allowing for dense icepacks on the rivers to melt just enough for us to paddle through without having to portage gear to the next put-in.

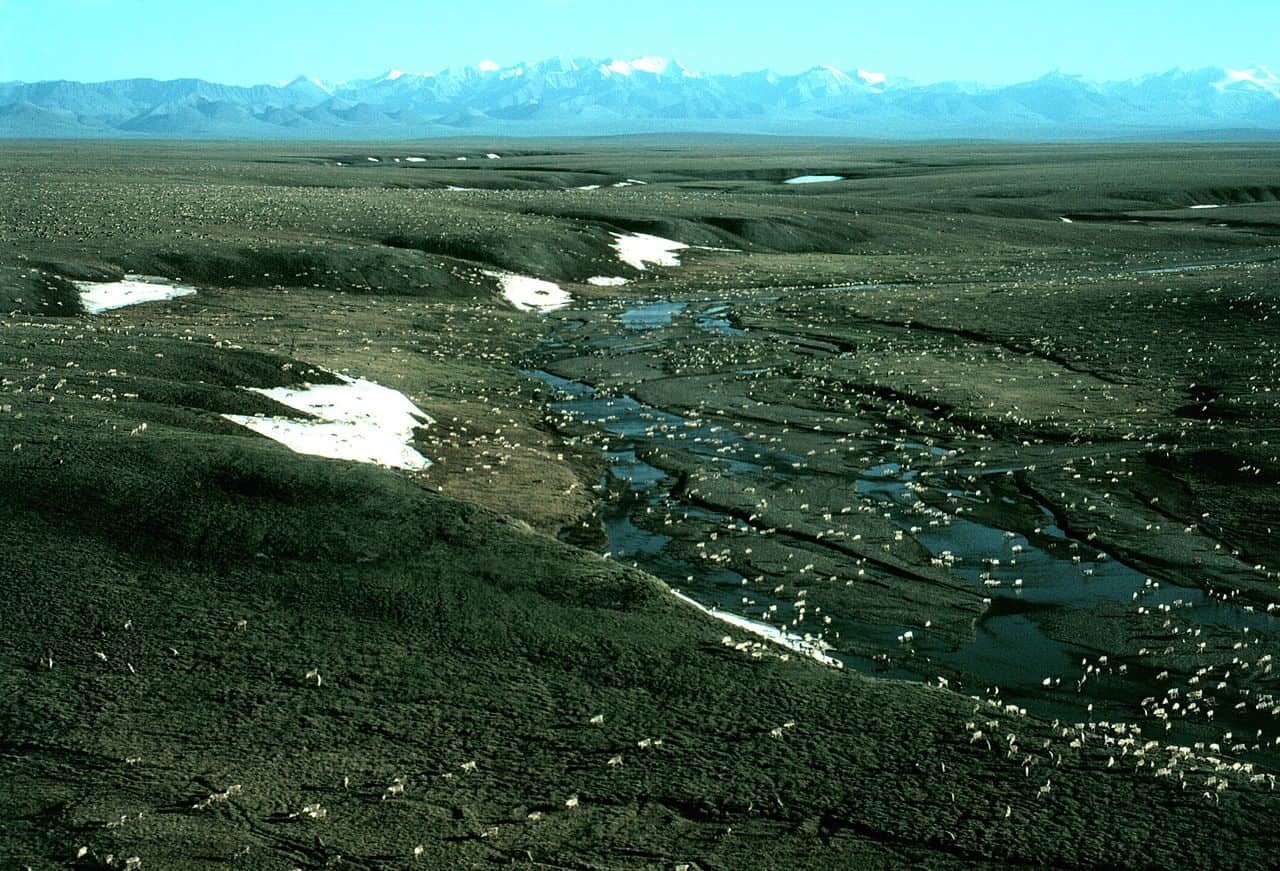

Covering more than 19 million acres, the ANWR is North America’s largest wildlife refuge. Bush planes are the quickest mode of travel into the refuge, but in a raft you can stop and hike to potential bird-watching locations wherever you want to and camp along the way. Late June through July is the best time to visit the refuge, because the sun never sinks below the horizon, so you can maximize the birding potential. The refuge is also home to 45 mammal species, including polar and grizzly bears, wolves, caribou, moose, Dall sheep, musk oxen, Arctic fox, and Arctic squirrels.

Where Rivers Converge

We camped on a grassy knoll overlooking the convergence of the Upper Marsh Fork and the Canning River. At their confluence, several wide channels braided off downriver, creating multiple gravel bars where red-breasted mergansers, long-tailed ducks, and glaucous and mew gulls congregated to roost in the abundant sunshine.

Hiking along the sandbars that supported massive icepacks, we found semipalmated plovers displaying their broken wing dance, desperately trying to lure us away from their nest sites camouflaged on the gravel bars. We located a gyrfalcon nest high in the cliffs above, and immediately we heard the alarm call, a guttural kak, kak, kak from the world’s largest falcon, directed at the spotting scopes and binoculars below.

Bouncing down the Canning River, my bright blue pack raft scraped across thick gravel bars and thrashed through spindly willows hanging over the banks of the river, while I kept a lookout for the numerous bird species in the refuge—the last huge swath of northeastern Alaska not open to oil drilling.

One seabird that we came in contact with for long stretches throughout the higher elevations in the refuge was Arctic tern. I was initially surprised to see them in the mountains, but there were quite a few of them nesting on gravel bars and roosting on tree limbs wedged between boulders in the runnel.

One tern in particular hovered above me, swooping down several times while tapping my head. That wasn’t enough, though, for the brazen seabird. Eventually, it dove at my blue pack raft and pecked at the bow with its sharp bill. For a moment, I thought it had punctured the bow and I had sprung a leak. It made only one attempt like that and then flew off, apparently satisfied that it had driven me off from its nearby nest—but not as satisfied as I was that I could continue paddling and was not stranded on a gravel bar with a deflated raft.

As we left the mountains behind us, all we could hear were the blades of our paddles piercing the shimmering, swift-moving waters and the distinct, harsh kak, kak, kak of a peregrine falcon. It felt like the world’s fastest flying bird was seeing us off before we rafted toward the vast coastal plain.

The Coastal Plain

The refuge is split by the Continental Divide. North of the divide in the Arctic watershed is the vast treeless tundra that extends across the entire coastal plain. Of the 180 documented species of birds in the refuge, 155 of those species are found on the coastal plain. Many of these species migrate from all over the world to breed and nest in the refuge.

High on the banks of the Canning River, we saw Pacific golden plovers dancing around a rack of caribou antlers. Where we pulled over for lunch, a northern wheatear hopped in and out of its nest site, a limestone slab only 10 feet from our raft. The most commonly seen birds on the tundra were the Lapland longspurs that appeared around every bend in the river.

We saw fast-moving caribou loping across the spongy tundra, flushing out coveys of Arctic warblers, their loud, vigorous, often-musical trills carrying across the tundra. A bevy of willow ptarmigan foraged along the banks of the river, following one another in a small procession.

After converging with the Staines River, we finished the day pitching our tents at the end of the runnel only several miles from the Arctic Ocean. After getting settled, I lit out on my own, hiking to the ocean meandering through a maze of tranquil ponds. We were now in a region of the refuge known as “1002.” It’s a 1.6 million-acre region between the Beaufort Sea and the Canning River. This region of the refuge has been a topic of hot debate over whether to drill for oil and gas. The vast amount of bird life alone is cause for continued preservation.

There are 34 species of shorebirds documented on the coastal plain, and surveys put their numbers at over 200,000. Pectoral sandpiper, dunlin, and red phalarope were tiptoeing in the shallows, and tundra swan and Canada geese waddled from pond to pond. There was one bird, though, that I was pleasantly surprised to hear before I saw it. There was no mistaking the loud rattling bugle of a sandhill crane. I spotted it wading between a series of glassy ponds near a barrier island on the Arctic Ocean, but they’re a rare summertime visitor to the refuge.

I walked the narrow barrier island clinging to the edge of the coastal plain, a flotsam of bleached driftwood, skeletons, caribou antlers, and passing ice floes. A ruddy turnstone wouldn’t budge from its nest. A flock of common eiders buzzed by me just a stone’s throw off the coast. From there, I followed grizzly bear tracks back to the coastal plain.

When I reached the serenity of the ponds, I could hear the simple wail of a red-throated loon. I located this smallest of the loon species, with two young following close behind it. Sharing the pond were a pair of northern pintail and a green-winged teal.

It was 3 a.m., and the sun was at its lowest point on the horizon. It was the last morning of the trip, as a warm glow was cast across the coastal plain—a bird watcher’s paradise clinging to the short Alaskan summer.

Chuck Graham is a freelance writer, photographer, and birder, and leads kayak tours at Channel Islands National Park. He lives in Carpinteria, California.