1. Spruce Grouse

The spruce grouse, at about 16 inches in length, is similar in size to the more familiar ruffed grouse, but is a bit chunkier. Males are brown with a black neck and throat, white spots on the belly, white markings on the throat, and a bright red wattle over the eye that enlarges during mating display, when the bird also spreads its tail and puffs out all its feathers. Females are generally nondescript mottled and barred gray and rufous, with white markings on the sides of the throat.

The spruce grouse is an uncommon to rare permanent resident, found primarily in boreal forest. Boreal forest is patchy in Michigan, and is most prevalent in the Upper Peninsula. Some areas of jack pine forest in the northern Lower Peninsula also support this species, but it is nearly impossible to find there as entry is restricted because it shares the habitat with the federally endangered Kirtland’s warbler.

They are surprisingly quiet and difficult to see for such a large bird, spending most of their time on the ground, and the fact that they rarely flush unless almost stepped upon makes the search even more difficult. Walking slowly and quietly through suitable habitat until one is seen is usually the best strategy, and once found the bird will often reward the bird watcher by staying put, or even walking out into the open, seeming to ignore the observer.

In April, spruce grouse are at their peak of courtship activity, and at that time are perhaps easier to find, though they can be chanced upon throughout the year. Some have said that wearing red laces in your shoes might actually attract a male spruce grouse; apparently the hormonally charged males during the peak of display will investigate any bright red object, presumably mistaking the laces for the enlarged red wattle above the eye of a rival male! The Vermillion Road near Whitefish Point has traditionally been a reliable spot for finding spruce grouse. Other areas of boreal forest that could be productive include the Yellow Dog Plains near Marquette, the boreal forest near Trout Lake, and the Kingston Plains in the western Upper Peninsula.

2. Sandhill Crane

This tall, stately bird, tanding nearly 5 feet tall, has long legs, all gray plumage, with a red patch on the forecrown, can be confused with nothing else. The sexes are similar. Sandhill cranes fly with their long necks and legs extended and flap with a distinctive upward flick of the wings. Their loud, bugling calls are among the most stirring sounds of Michigan’s wetlands in summer and during fall migration.

The sandhill crane is a fairly common summer resident and a locally common migrant. They breed nearly throughout the state, but with two main population centers, one in the central southern Lower Peninsula between Jackson and Battle Creek, and the other in the eastern Upper Peninsula in the Rudyard area. Another, more dispersed breeding population occurs in the west central Lower Peninsula between Manistee and Big Rapids. The birds arrive in February or March, and depart in late November or early December. In recent years, a few individuals have overwintered in the southern part of the state.

During fall migration, sandhill cranes stage in wetlands, sometimes in large numbers. Two of the best places to see this spectacle are the Phyllis Haehnle Sanctuary northeast of Jackson, and the Bernard W. Baker Sanctuary northeast of Battle Creek. From mid-October through November, counts of several thousand birds are typical at these locations. Watching them come flying in to roost in the late afternoon in increasingly larger groups is a stirring sight, not soon forgotten. The birds also breed, though in lower density, at these two sanctuaries as well as in surrounding wetlands and agricultural areas. They have been expanding into new breeding areas over the past 20 years.

3. Piping Plover

This small shorebird, about 7 inches in length, is often described as the color of dry sand above and white below. Adults have a narrow black band running around the beast and back of the neck, a white forehead, a small black band across the crown, dark eyes, a short orange bill with a black tip, and yellowish-orange legs. In flight, they show a white rump, a white tail with a broad black tip, and black flight feathers with a prominent white band. Juveniles lack the black breast and crown bands, and have all black bills.

The piping plover is a federally endangered species that is a rare summer resident in Michigan. Nest sites and numbers vary from year to year, currently about 40 to 50 pairs statewide. Piping plovers arrive on their breeding beaches in late April or early May, breed during the summer months, and depart the state for their wintering grounds in August and September.

In the Great Lakes, piping plovers nest on undisturbed sandy beaches, of which precious few remain. They are most easily found during the breeding season where such beaches have been preserved and are protected from human disturbance. Sites where they have nested include the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Wilderness State Park, near Munising, and near Whitefish Point. Nesting sites are closely monitored, and will usually be posted as closed to entry. These signs should be obeyed, as they protect the bird’s from being disturbed, and their nests from being trampled. At most sites, the birds can be viewed from outside the closed areas.

4. Great Gray Owl

A very large all gray owl, about 27 inches in length, with a very large head, large facial disks, a black and white patch in the area of the chin, and piercing yellow eyes. They are frequently active in daylight. They are nearly unmistakable.

About every three to five years, populations of mice and voles in the Far North crash, which force their predators farther south in winter than normal. These forced migrations are called irruptions. The great gray owl is mainly an irruptive winter visitor to Michigan, occurring from December through March. Occasionally, after large irruptions, some birds may be seen into late spring or even early summer. Some winters they are completely absent from the state.

When present, great gray owls are usually easy to find because they often perch in the open on the edges of open fields, where they hunt their rodent prey. Few of these birds have encountered human beings before, and some are probably near starving, so they are typically quite tame and approachable. Most irruptions do not take these birds farther south than the Upper Peninsula, and the best areas to search for this species includes the open fields south of Sault Ste. Marie, as well as Neebish Island and Sugar Island in the St. Mary’s River.

5. Pileated Woodpecker

Our largest woodpecker, at 17 inches about the same size as a crow. The body is all black with a black-and-white striped neck. The underwings are all white, and the upper side of the wings have a small white patch. The males have an all red crest, pointed at the rear, and a red whisker mark. Females have crests that are red toward the rear and dark at the front, and have a black whisker mark. Pileated woodpeckers, as do all woodpeckers, fly with a bounding flight and perch vertically on tree trunks where they hammer at the bark hunting for insect prey.

The pileated woodpecker is an uncommon to fairly common permanent resident in Michigan. It inhabits mature forested areas with larger trees. It is scarce in much of the southern Lower Peninsula, but as suburban areas are becoming reforested this species is reclaiming portions of its former range. Any larger forested area throughout the state will hold at least one breeding pair of this magnificent woodpecker. Despite their size, they can be difficult to locate as they range quite widely, and often feed rather quietly. Large, rectangular excavations in tree trunks are evidence of the presence of these birds. Sometimes they can be located by their loud, somewhat maniacal calls, sounding something like a northern flicker on steroids.

6. Carolina Wren

The largest wren found in Michigan, at about 5 1/2 inches in length. Easily recognized by its rufous-brown upperparts and whitish underparts with a buffy belly, long, pointed, and curved bill, and broad, bright white line over the eye. The very pleasing song, tea kettle, tea kettle, tea kettle is somewhat similar to northern cardinal or tufted titmouse, but unlike any other wren in the state.

The Carolina wren is an uncommon to fairly common permanent resident, generally found south of Grand Rapids and Flint in the southern Lower Peninsula. It is most easily found in residential areas, but also in wooded areas. Winters with deep snow, most recently during the late 1970s, have eliminated this species completely from the state in the past, but the birds re-colonized by mid-1980s. Single birds have recently reached as far north as the Upper Peninsula during northward movements in fall.

This species is usually easy to find by listening for its song. Most well-wooded parks and residential areas in the southernmost portions of Michigan have resident Carolina wrens. Some places to check include Fairlane Woods at the University of Michigan – Dearborn, the Kleinstuck Preserve near Kalamazoo, and Sarett Nature Center near Berrien Springs.

7. Golden-winged Warbler

This is one of our most boldly patterned warblers, with a gray body, a black ear patch surrounded by white, a black throat, bright yellow crown, and true to its name, broad golden-yellow wing bars. Females have the black areas replaced by gray, and have duller yellow. One of our smaller warblers at slightly less than 5 inches in length, the golden-winged warbler is often detected by its bee buzz buzz buzz song.

The golden-winged warbler is an uncommon and declining summer resident, most numerous in the northern Lower Peninsula and parts of the Upper Peninsula. They arrive in May and depart by mid-September. It is more local than the blue-winged warbler, and its range retracts northward as the blue-winged’s expands and hybridizes with it. These hybrids are frequent enough that they too have been given names; Brewster’s warbler, which is more frequently encountered, and Lawrence’s warbler, which is rarely encountered.

In the natural process of succession, open fields become shrubby, and eventually the shrubs get replaced with trees, and becoming a forested area. The golden-winged warbler seems to prefer the “middle-aged” shrubby phase for its breeding habitat, while blue-winged warblers can use the earliest shrubby habitats right through to the latest.

Thus, the golden-winged warbler may be more specialized than the blue-winged, and so is vulnerable as the blue-winged continues to increase its range northward. Suitable golden-winged warbler habitat often has the character of a shrubby wetland, as well as a coniferous component to the vegetation. Some good sites for golden-winged warbler in the southern Lower Peninsula include the Gratiot-Saginaw State Game Area and the Port Huron State Game Area. Farther north, look in appropriate habitat in areas such as the Huron-Manistee National Forest, especially in the western portions (Manistee section).

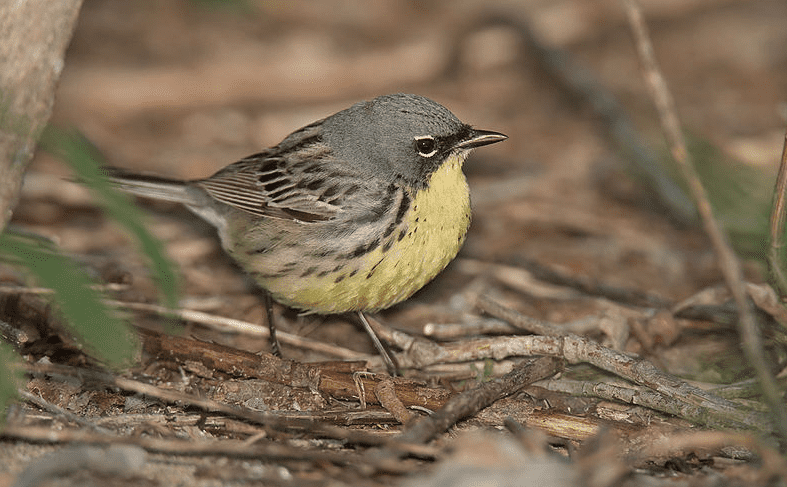

8. Kirtland’s Warbler

The Kirtland’s warbler is one of our largest warblers, at slightly less than 6 inches in length. Its upperparts are blue-gray with black streaks on the back, white wing bars, and a broken white eye ring. The blue-gray tail has white spots on tips of the outer two tail feathers. The underparts are yellow from the chin to the belly, and white under the tail. The breast and sides show prominent black streaks. The song is one of the loudest and most cheery of any warbler, a richly warbled chur chur CHEE CHEE wee wee.

The Kirtland’s warbler is Michigan’s most unique bird because it breeds nowhere else in the world and is listed as a federally endangered species. Breeding is restricted to jack pine forests between about 6 and 20 years of age in the north central Lower Peninsula, largely within the Huron-Manistee National Forest. The bulk of the population breeds in Crawford, Oscoda, Alcona, and Ogemaw counties. Jack pine cones do not open to allow the seeds to drop to the ground unless they have been exposed to fire, and the warbler’s requirement of younger trees has earned it the nickname “bird of fire.”

In 1971, a survey turned up only 201 singing males, which was half the number detected on surveys in the 1950s. Numbers decreased further to 167 singing males in 1974 and 1987. The factors causing the declines were determined to be loss of habitat due to fire suppression, and extensive nest parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds, which moved into the breeding areas due to habitat fragmentation.

Habitat management, through controlled burns, has increased the available habitat, and cowbird control through capture and removal has reduced parasitism levels. These management methods have slowly allowed the population to increase. One recent controlled burn, in the Mack Lake area, got out of control and nearly burned down the town of Mio among the nearly 24,000 acres burned. This large area of new habitat was colonized when the trees were six years old, and gave the population a significant boost.

In recent years, the number of singing males has exceeded the conservation goal of 1,000, with 1,083 in 2001, 1,052 in 2002, 1,204 in 2003 and 1,341 in 2004. A few pairs now breed in several counties in the Upper Peninsula as well.

The best way to see Kirtland’s warblers is on a National Forest Service tour out of Mio, or on a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service tour out of Grayling. These tours are run between about May 15 and July 4, and can be a very rewarding experience as you are taken into areas generally closed to the public where good views of the birds can often be had. And you will learn about the interesting life history and conservation efforts of this species.

While it is not illegal to find a Kirtland’s warbler on your own by driving the forest roads that are open to the public, it is illegal for you to leave the road to pursue them or play tapes to attract the birds. Pets must also be prevented from entering the breeding areas, as the birds nest on the ground under the lowest branches of the jack pines. The birds are often curious and will sometimes approach observers standing quietly with enough patience, and are easily detected from a distance by their loud and persistent singing.

Kirtland’s warblers arrive on their breeding grounds sometime after May 10, and most have departed for their wintering grounds by early September. They winter in the Bahamas, with most being located on Eleuthera and a few on Andros. Until recently they were almost never observed on their wintering grounds. As the population has increased, sightings of migrants have also increased. Formerly, this species was almost impossible to detect in migration, but in the past ten years it has been found annually at migrant traps such as Crane Creek State Park, Ohio, Pt. Pelee National Park, Ontario, Canada, and Tawas Point State Park, Michigan.

9. Prairie warbler

This small warbler, slightly less than 5 inches in length, is largely olive-yellow on the upperparts with a bright yellow eyebrow and yellow crescent below the eye, and black markings through the eye and below the yellow eye crescent. The back shows reddish streaks with exceptionally close views. The tail shows large white tail spots. The underparts are bright yellow, whitish under the tail, and with prominent black streaks on the sides up to the side of the neck. Females are duller, lacking the black markings on the face and with the bright yellow replaced with whitish. The song is a rapid, slightly buzzy, rising series of whistles, zoo zoo zoo zee zee zee ziii zii.

The Prairie warbler is widely distributed throughout the eastern U.S., but is at the northern limit of its occurrence in Michigan, where it is a rare migrant and summer resident, arriving in May and departing by early September. Listed as threatened in Michigan, there are probably fewer than 200 breeding pairs statewide. Despite its name, the Prairie warbler does not breed in prairie anywhere in its range.

In the southeastern U.S., where it is perhaps most common, it nests in coastal scrub and even in mangroves. In the interior portions of its range, it nests in open or semi-open shrubby habitats. In Michigan, the species nests almost exclusively in pine woodlands covering sand dunes with a shrubby understory. The warblers nest on or near the ground, so caution is advised when looking for them on the breeding grounds.

The largest breeding population is at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, with birds also breeding at Nordhouse Dunes, Oval Beach near Saugatuck, Grand Mere SP, and Warren Dunes SP. Prairie warblers have occasionally been found at the Allegan State Game Area and the Island Lake State Recreation Area.

10. Connecticut Warbler

This is a large warbler, nearly 6 inches in length, and is almost always found walking on the ground; the Connecticut warbler never hops and is rarely seen perched in shrubs or trees. The back, wings, and tail are olive-green, and the head, throat, and upper chest are all gray, forming a distinct hooded appearance. There is a distinct, complete white eye ring. The lower breast, belly, and under tail are bright yellow. The legs are sturdy and bright pink. Females are slightly duller. The song is a staccato chippy chuppy chippy chuppy chippy chuppy.

The Connecticut warbler is a rare breeding species in Michigan, but is more often encountered during migration, when it is rare in spring and fall. Spring arrival is later than that of many other warblers—typically in the last half of May into early June even in the southern portions of the state. In fall, most are detected at banding stations, but they seem to move south in greatest numbers in mid-September. Connecticut warblers breed on the edges of spruce bogs, which are very patchy in distribution in Michigan.

Formerly, breeding Connecticut warblers were detected in portions of the extreme northern Lower Peninsula, but there are few recent records. Breeding birds are found principally in the Upper Peninsula. Even there, they are often shy, skulking birds that are more often heard than seen. Complicating the issue is the fact that Nashville warblers, which are similar in appearance, and northern waterthrushes, which can have similar-sounding songs, are both common breeders in the same habitat as the Connecticut warbler.

Connecticut warblers can be found at many locations in migration, though many sites do not record them every year. Some places that have proven fairly consistent include the Kleinstuck Preserve near Kalamazoo, the Nichols Arboretum in Ann Arbor, Fairlane Woods at the University of Michigan in Dearborn, Metro Beach Metropark near Mt. Clemens, and Tawas Point State Park. Breeding birds are most frequently found in the Upper Peninsula north of Trout Lake, at the Baraga Plains, and rarely in the Porcupine Mountains State Park.